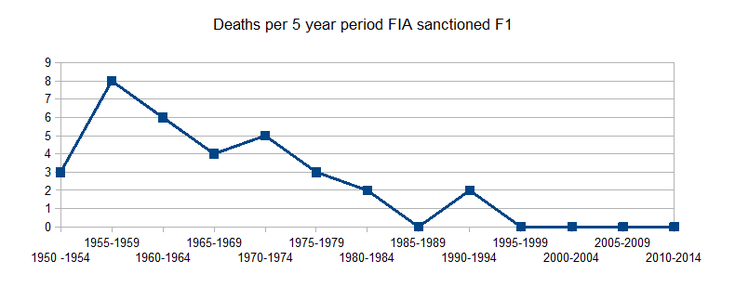

If you think that F1 is dangerous then you’re right. Obviously. Safety in Grand Prix racing has much improved since the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna 20 years ago. This is thanks largely to the technology drive powered by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) along with Formula One Group (FOM) who have worked hard to ensure high levels of driver protection when normal accidents occur.

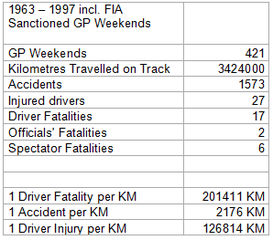

Much of the technology used to protect drivers has trickled down into road cars and despite numerous deaths scattered throughout the history of F1 many lives have been saved on public roads. Basic standard safety systems used if F1 have not always been mandatory requirements. Helmets and overalls became obligatory in 1963, stipulations on seatbelts came into force as late as 1972, the permanent medical centre at every racing facility was only introduced in 1980 while computer analysis of ‘high risk’ circuits began following F1’s darkest weekend at Imola in 1994.

Jules Bianchi’s collision at Suzuka was one that can be defined as a normal accident. It was unlucky but the events which led to the crash formed part of a system of cascading failures across the Japanese Grand Prix. These were:

1) Drivers not slowing enough during the yellow flag phase on lap 41 – the FIA are going to introduce a controlled slow down system to regulate this.

2) Drivers not driving within the boundary of the conditions – Ericsson spun off under the safety car early in the race.

3) Equipment that doesn’t fall into the crash structure design of a F1 car being present inside the confines of the circuit. Impacts into recovery vehicles are not part of the FIA crash testing process. The cars are very well designed to protect drivers in collisions with tyre walls and barriers.

4) Some drivers have complained that the wet weather tyres do not remove enough standing water. Bianchi had intermediate tyres at the time of the crash.

5) Fixed cranes stationed behind the crash barrier were not present at that corner.

6) The run off area at turn 7 may not be wide enough to neutralise the speed of the cars in the event of an accident – other tracks have had modifications to their run off areas to accommodate cars leaving the circuit at high speed.

7) The safety car was not called early enough following Sutil’s crash on lap 41.

New safety measures have generally led to a more competitive championship. However the FIA decided to ban performance enhancing electronic technology for the start of the 1994 season. This resulted in many of the cars that year being twitchy and difficult to control at high speed. With greater horsepower and torque than the previous year but a lower level of car stability many drivers were vociferous in their concerns including Senna who claimed it would be a “season with many accidents”.

Average speeds have accelerated rapidly through the decades as have safety standards. Just how safe is the current era of F1?

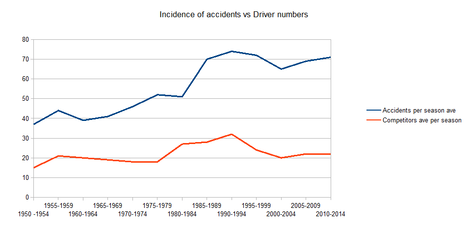

The Peltzman effect appears to be present in F1. Between 1963 and 1985 just over 57% of accidents occurred due to mechanical breakdowns, failures or tyre delamination. This figure began to change as the cars became safer. From 1987 onwards around 69% of accidents have been brought about by driver actions. As the cars and tracks have become safer drivers have started to take more risks. From the mid 90s onwards F1 has seen a reduction in the number of teams on the grid with an average of 22 drivers taking part at each race weekend. As a result competitiveness has increased along with safer machinery but the number of accidents per season has grown to a mean of 70.2 from the period 1985 to 2014 (2014 season currently in progress). Though the mean has increased accidents are much less violent now than in previous decades. Today the cars can tap the barriers and continue with light damage where as prior to the mid 90s in similar collisions they’d fold like a piece of paper.

The FIA will continue their great job of reducing the dangers of motorsport but it’s a balancing act as competitive drivers are hard wired to push at all times.

Let’s hope Jules makes a fast and full recovery and sparkles again in F1 soon.

Data sources: FIA & Grand Prix Records.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed