We hope all our readers have a very enjoyable summer.

|

As is customary at this time of year, we will take our summer break and return on Tuesday 6th of August 2019.

We hope all our readers have a very enjoyable summer. By David Butler

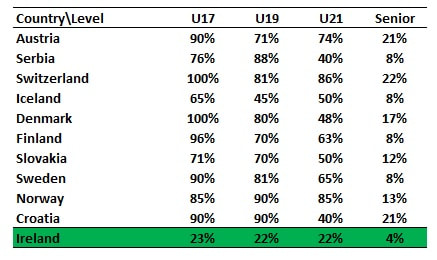

Some of the last entries below concern the future of Irish soccer talent development. In short, I argue that focus should be placed on developing our U13 to U19 divisions with the aim of continually exporting our best to a variety of leagues (not just those in England). The league of Ireland senior level should play a secondary role. This type of structure would be in the tradition of European counterparts that are ranked similarly to us. Below are some stats that give an insight to the ability of other European countries to retain talent in their national league structure and subsequently draw only a few domestic players at a senior level. I sampled a selection of countries relatively similar to Ireland (population and coefficients), many of which were cited in the original entry below. The table shows estimates for the percentage of players in an underage national squad that are attached to a domestic club. Again, it’s pretty clear to see a trend for all nations except Ireland. Players from other countries generally fly the nest later. Most Irish players have left these shores by the time they are eligible to play U17 (assuming they are trained here to begin with). At present, the temptation to move to the UK at a young age is as strong as ever. The aim should be to retain this talent domestically for a longer developmental period prior to exporting. Of course, this would require investment and the appropriate structures. Achieving this retention should be a primary goal for the national league. Albeit difficult to emulate the facilities, standards and the potential monetary rewards offered by UK clubs, policy should focus on providing a strong developmental process domestically that would at least give players a difficult choice regarding whether to move now or wait. By Robbie Butler

Last year Croatia reached the Final of the FIFA World Cup in Russia. The team is presently 6th in the FiFA World Rankings. With a population of just over 4 million people and a land area less than two-thirds the size of Ireland, many asked why the Republic of Ireland could not also achieve these feats. Those that watched the Republic of Ireland versus Gibraltar recently would probably admit the team is a very long way off reaching the World Cup Final. But if a country with a smaller population and area can do it why not us? There are a number of differences between the two countries that make comparisons tricky. Firstly, Croatia has one dominant team sport - football. Ireland has four - Gaelic Games, rugby and football (or soccer). The national league of Croatia, at first glance, is not too different to Ireland. A top division of 10 teams in both countries, coupled with low attendances at domestic games, means there are a number of similarities. What is different however is the composition of the teams. Ireland is very much about growing indigenous talent. More than 90% of players in the League this season are from this island. This translates to just 58% in Croatia. EU players and non-EU (of which there are about 1 in 4) players constitute the remainder. In economic terms, Ireland does not tend to import talent. This is not the case across the vast majority of European leagues, Croatia included. The export side is also interesting. For many years, Ireland benefited from favourable "terms of trade", and exported almost exclusively to the UK. From the 1940s to the 1990s, Irish players found homes at the best English clubs. However, since the mid-1990s the favourable trading conditions have vanished. Ireland has not adjusted however and we continue to export almost exclusively to a single market - England. Not necessarily to the Premier League anymore, but the Championship, League 1 and so on. A more productive route might be to do what almost all others in UEFA do - export to all countries. A broadening of our horizons, both in import and export terms, is something we should all consider. It might be our first step to becoming more like Croatia. By Robbie Butler

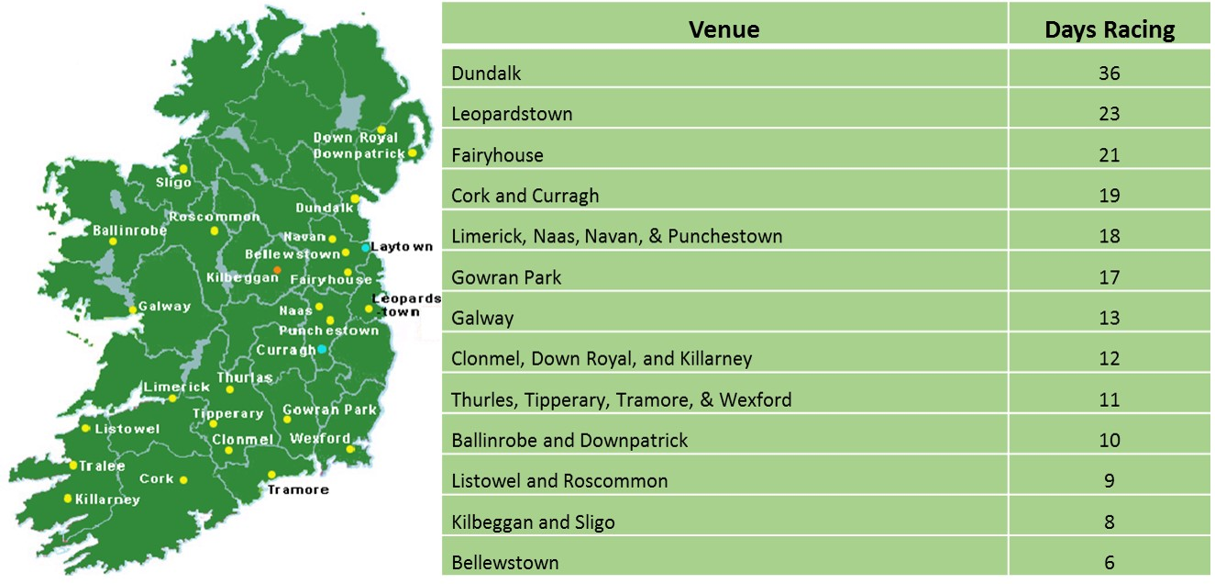

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations is a masterful exploration of political economy by the late Harvard professor David Landes. Very early into this 650 page text the author raises the issue of Eurocentrism - a worldview that is inherently biased towards Western civilization, or western Europe (depending on ones' definition). At a recent event at the University of Oxford, UEFA President Aleksander Ceferin appeared to suggest that such Eurocentrism is alive and well in European football. The former Slovenian lawyer said the following about the recent Europa League Final stage in Baku, Azerbaijan: "We decided a year and a half ago that we play in Baku, which has a modern stadium of 70,000. I think there is only one stadium in England that is bigger....If somebody asks me why we played in Baku, I would say: 'People live there. Homo sapiens live there...They had to watch the game at 11pm because of the time difference but nobody complained...If we have two Azerbaijani teams playing in London nobody would complain. They would come and play without any problems...We have to develop football everywhere not England, Germany only...[the] Europa League and everything else should be shared with the others who love football." Ceferin's comment was largely motivated by the negativity surrounding the Final last month between Chelsea and Arsenal. Much of the commentary of the Final focused on the empty seats at the stadium and lack of atmosphere. Many questioned why fans had to travel so far to see their teams complete. A vivid example of Eurocentrism? Although the 'big 5' have some of the largest populations in Europe, UEFA represents 55 full member associations . The association’s strategic plan from 2019-2024 has four pillars one of which aims to “Promote and develop football infrastructure across Europe”. Spreading the game is a mission that has been at the core of UEFA, and FIFA for that matter, for many years. This is why cities such as Baku get the chance to host major finals. It was impossible to predict who would play in Baku, and the distance fans had to travel was probably accentuated by the fact that Chelsea and Arsenal are under 10 miles apart. Despite what people may now believe, this was not a poorly attended final. In fact, it is the 3rd best attended Europa League Final to date. Countries on the periphery of Europe are just as entitled to hosts these games as the England, Germany or Spain. In fact, I recall not so long ago a country on the edge of Europe hosting the Europa League final. I was there when two Portugesse teams just 55 km apart, were forced to travel a round trip in excess of 2,700 km. The location? Dublin. I don't remember the Portuguese having any problems. 45,391 people showed up in the Aviva that night. There were 5,979 more in the Baku Olympic Stadium. By John Considine At the recent Sport Economics Workshop held in University College Cork, David Forrest presented a paper titled “Spectator Demand for the Sport of Kings”. Afterwards, in the company of David and Rob Simmons, I asked about the seemly small figures that David had presented for the average number of race meetings per track and the average number of times horses raced. A comprehensive explanation followed. It is always a privilege to hear David Forrest and Rob Simmons explain some of the economics surrounding horse racing. Prompted by the discussion I decided to examine the Irish horse racing schedule for 2019. What follows are some of the numbers on this schedule. There are 80 days on which racing is not scheduled to take place. On the remaining 285 days, there are 211 days on which only one race meeting will take place, 73 days on which two race meetings take place, and one day on which three race meetings are scheduled to take place (December 26th). In terms of consecutive days racing at a particular venue then Galway and Listowel are unusual in that each venue has a seven days of consecutive racing. Killarney and Punchestown have 5-day events. However, the majority are stand alone single days racing. Racing is scheduled to take place at 25 different venues. The distribution of the schedule across these venues is listed in below. The list is presented in descending order by number of race days. The all-weather track in Dundalk tops the list. When one hears the term “all-weather” then one thinks about the underfoot conditions. However, it is the presence of artificial light that is as important in explaining Dundalk’s number of events. There are 147 “evening” meetings. One hundred and fourteen (114) of these are held in tracks other than Dundalk during the second and third quarters of the year. However, for the first three months of the year, and the last three months of the year, the only evening fixtures are held in Dundalk.

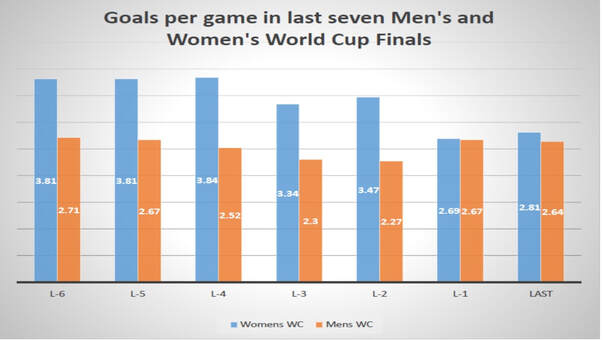

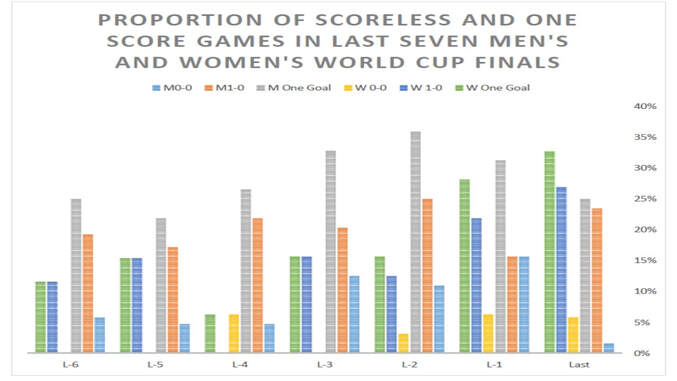

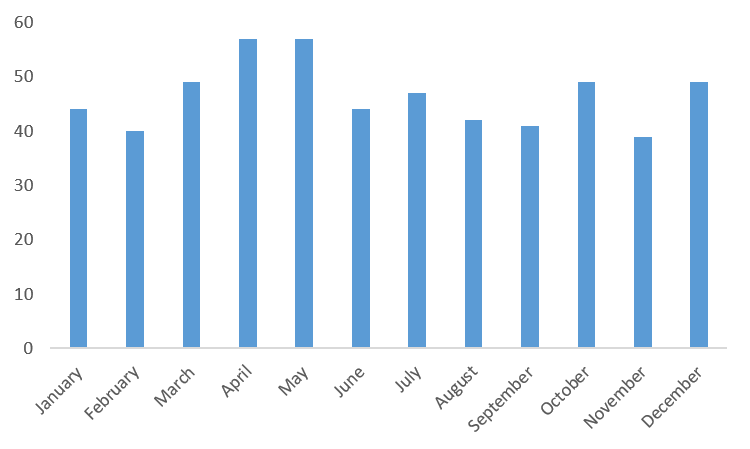

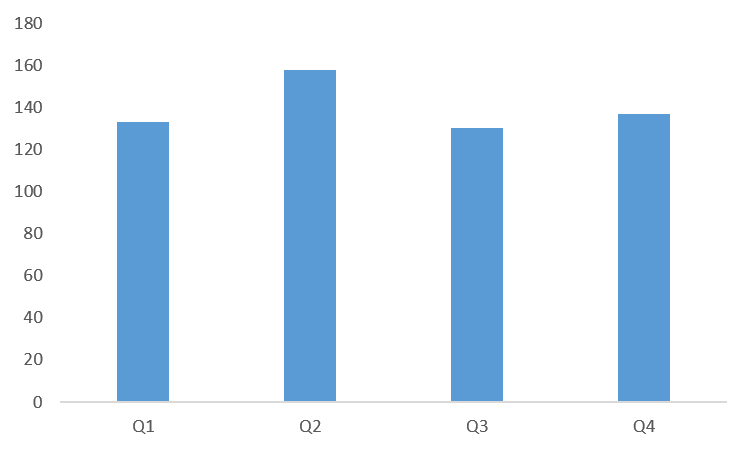

by Declan Jordan  The FIFA Women's World Cup in France continues to throw up great games and surprises. The women's game is in the spotlight and, while the football has been great, there are frustrations at FIFA's organisation and commitment to the game, pay inequality, and sexism. It is perhaps unavoidable that the competition and women's football generally is compared to the men's equivalent. It is not difficult to find patronising commentary on television and in print media whenever women's football is covered. There is almost surprise, particularly in the Irish and UK coverage with which I am most familiar, that professional athletes are technically skillful, competitive, and committed. (There are similarities in the treatment of female football analysts, referred to by Alex Scott here. That it is surprising that someone who has played 140 times for her country should be insightful about the game says a lot about our attitudes to women in football). Perhaps these attitudes are based on an outdated notion of the women's game, though there are certainly socialised stereotypes at play as well. In a recent article in the Irish Examiner, Larry Ryan referred to a comment by England striker Toni Duggan that she was somewhat heartened to see the anger from opposition fans when she celebrated a goal she scored for Barcelona. For her it showed that the game mattered and the players were being taken seriously. The article though warns that the women's game should try to avoid going down the road of the men's game and should instead try to hold on to the values of inclusion, loyalty, and community. This doesn't mean of course that the women's game will not get more competitive, skillful, and demanding. The negative stereotypes will take time to break down of course, but it is interesting to review the data on previous World Cup Finals, both women's and men's, to shed some light on the game's development.The USA's 13-0 demolition of Thailand has led to some suggestions that the World Cup is losing credibility and the increase in teams from 16 to 24 will damage the tournament with more one-sided games. The data doesn't back this up however. The graph below shows the goals per game at each of the last seven World Cup Finals tournaments (the last men's tournament was 2018 in Russia and the last Women's tournament was in 2015 in Canada). For information, in the first round of group matches in the current tournament (12 in all) to Tuesday June 11, there have been 3.17 goals per game. Excluding the USA-Thailand game the ratio is 2.27 goals per game). It is striking how the ratio of goals per game has declined over the seven tournaments. From having just over a goal more per game, the women's tournament has now reached a comparable level with the men's. Whether this is a positive or negative development is unclear, though even as the number of countries in the finals of the Women's World Cup has increased goals have become more difficult to come by. Similarly with the number of low-scoring games, there has been a narrowing in the differences between the tournaments over time. The Women's World Cup Finals did not see a scoreless match until the final day of the third World Cup (in 1999) when both the third place play-off and the final ended nil all. Up to the last World Cup finals there have been nine scoreless matches. There has been one more in current tournament when Argentina parked the bus against the favoured Japanese. In comparison over the last seven men's tournaments there has been an increase in scoreless matches from close to 5% of matches to 15% in 2014. In 2018 there was only one scoreless match. It is interesting though to include the number of games that have ended 1-0. The green bar in the graph below shows the proportion of matches that have had one goal or less (within 90 minutes). The women's World Cup has gone from about 12% of matches in the first tournament in 1991 (and only 6% in 1999) to a third of matches in 2015. (A third of the 12 games in the current tournament have had one goal or less). The grey bar shows the corresponding data for the men's tournaments. Rising from 1994 to 2010 before falling in 2014 and 2018, the level has been between about a quarter and a third. The women's rate has exceeded the men's in the most recent tournament. It may be that the fewer number of participants in the women's finals means the best teams are playing and the matches are closer. The number of teams taking part increased however in 2015 from 16 to 24. Adding the extra teams has not diminished the closeness of the games (measured by the proportion of low scoring games). It may instead point to an increase in standards - or at least a decrease in the variability of standards - at the elite level and the women's game converging with the men's game, whether for good or ill. The data may also point to greater levels of organisation in coaching and associated resources from national bodies for the women's national teams, and further posts may explore that idea. By Robbie Butler The FIFA Women's World Cup kicked off in France last week and for the first time ever all 52 games from the tournament will be shown live on free-to-air television in Ireland. This is an excellent opportunity to showcase women's football to a mass audience in Ireland. The importance of this cannot be underestimated and should increase the level of interest in Ireland for the women's game. There have been goals aplenty so far and not a single draw to date in the group stages. Tournament favourites and hosts France got off to an impressive start winning 4-0, while defending champions the United States will begin their quest for a record 4th World Cup crown tomorrow (Tuesday). Speaking to friends over the weekend that had been watching games from both this tournament, and the UEFA Nations League and European Championship qualifiers, a number of people observed that technical proficiency (close control, passing accuracy, dribbling, etc), rather than physical dominance, appear to be more obvious within these games. Given the need to be technically proficient, does that then mean the relative ages effects (RAE) are less to be present at this competition? The answer is no. RAE is almost always as visible in underage football for girls as it is for boys. When one considers adult teams across both gender RAE is almost never a factor. The data below presents the distribution of dates of birth for players at the World Cup in France. Broken down by month of birth (left-hand side) or quarter of birth (right-hand side) the distribution of birth dates is largely random. A closer look at the Nations League semi-finals and final would probably produce similar findings. While being born earlier in the year (regardless of gender) is advantageous for selection at underage teams, deselection for elite national teams is more likely for those earlier in the calendar year.

By David Butler

A lot has been said and written of late about the best way forward for Irish football (soccer). It is important to make a point in relation to elite development and senior international performance in the men’s game. This concerns the role of the senior domestic league. While the League of Ireland has a role to play in Irish football, the evidence would suggest it is remiss to consider it a place to systemically develop or draw talent from for our senior international team. This point is premised on the models of competing European nations. Looking at our competitors, it is clear that very few current senior internationals stay-on to play in their domestic league. Our opponents Friday night (Denmark) only have 4 players contracted to Danish clubs, 3 of whom are uncapped. There are many more examples from other nations similar to Ireland that take the same develop-and-export approach. Iceland (2), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1), Sweden (3), Austria (5), Norway (3), Slovakia (4), Switzerland (5), Portugal (7) are just some other cases where a minority of the senior squad is drawn from the domestic ranks. Ireland, like many of smaller nations, do not have the population or the national league strength to support a develop-and-retain model. Only the Big-5 nations and a handful of others with significantly larger populations such as Russia, Ukraine and Turkey adopt this type of model. The well-known Irish ‘problem’ is that players are drawn almost solely to British leagues. This is owing to a range of cultural and economic factors, and is partly due to the Republic sourcing English born talent. The solution to this problem is not to look inward but rather to break the tradition of exporting on mass to English clubs. My hunch is that player’s will receive greater developmental opportunities outside of British leagues. We can remedy the current mind-set of focusing on the UK. In turn, this will aid the development of future Irish talent. Historically, we have failed to export to other European countries. Developing policies to achieve this diversification of talent is needed. Our international competitors mentioned above manage to do this. They export talent to a diverse range of leagues. For example, the Iceland squad is represented by 14 non-domestic leagues, Bosnia and Herzegovina by 13, Denmark by 6, Sweden by 11, Slovakia by 14. This list goes on. With the exception of Sean McDermott, who is contracted to Kristiansund BK, and James Talbot (Bohemians), all other members of the current squad play in the English leagues. Of course, this is not a call to abandon the League of Ireland. We just need to taper our ambition for the developmental capacity of the senior game. Developing two or three clubs to the standard seen in other small European leagues would be a major achievement and should be a key goal. If developmental opportunities are on a par in two-three clubs to those in other small European leagues, the League of Ireland could be in a place to retain a minor amount of senior internationals. This is the structure for several European competitors and should be the aim for domestic football here. Dominance in the LOI would likely bring about balance problems, but it may be a necessary trade-off to get some of the trappings of dominance (e.g. improved player development process and entry to elite European competitions). This is seen elsewhere. For example, 2 of the 4 Danish based players in the squad for Friday night play with F.C. Copenhagen – they have won 6 of last 10 Danish Superliga and have finished 2nd in 3 of the last 10. Similar outcomes exist in Austria. FC Red Bull Salzburg have 8 won out of last 10 Austrian Bundesliga, and were 2nd twice. 4 out of the five current Austrian national players are contracted to the club. These examples go on - Switzerland for instance is dominated by FC Basel and BSC Young Boys. The few Swiss based senior internationals are often contracted to these clubs. Perhaps the Croatian approach is the best example to think about. They have a similar population to Ireland. At times they suffer from a ‘tramway’ league - like Ireland they have too many clubs based in the capital. Like us, they also suffer from low domestic attendances. While we have several similarities, our international fortunes have been very different since Croatia emerged as a major player at the World Cup in 1998. This is simplistic but the differences are interesting. In the tradition of other smaller European countries their current senior squad only sources 5 players from the domestic league but is represented by players playing in 11 other countries. Like the Austria, Denmark and the Swiss examples, they have historically dominant clubs in Dinamo Zagreb and Hajduk Split that develop and export talent but are strong enough to retain a minority. The take away message is that to improve senior international football, attention needs to be placed on developing our U13 to U19 divisions with the aim of continually exporting our best. The change however has to come in the form of players not solely being transferred to UK leagues. Developing the men’s senior league should be a secondary, long term objective to supporting a predominantly export based model. By assisting the emergence of dominants club(s) - which of course is far easier said than done – the Irish setup would develop a similar structure to other small European leagues. By John Considine Prior to last week’s Europa League final between Arsenal and Chelsea, there was plenty of debate about whether or not Petr Cech should be the Arsenal goalkeeper. It was to be Cech’s last game and there were rumours that he was to take up a non-playing position with Chelsea next season. It begged a few questions about Cech’s commitment to the Arsenal cause.

Contract situations, somewhat like the one Cech found himself in, are the subject of a recent paper by Daniel Weimar and Katrin Scharfenkamp. Published in Managerial and Decision Economics, the paper examines the effort that football players spend on behalf of their current team when they have already signed a contract to play for another team. The authors found a statistically significant 1.23% reduction in effort by such individuals. Crucially, this did not translate into a statistically significant reduction in team performance. Weimar and Scharfenkamp measure effort using the distance the player runs during a game (hardly a measure useful for goalkeepers like Cech). One of the more interesting elements of the paper is the discussion of why this measure was selected. For example, the authors note that the correlation between the distance covered by a player and the market value is low (r = -0.03). In addition, the authors go to great lengths to control for all sorts of potential other influences. Establishing a measure of individual contribution to team performance is not easy. And it can be more difficult in some sports than others. On the surface, one would imagine that the individual contribution is easier to identify in a sport like baseball than football. Yet, it is not straight forward in baseball as another recent paper by Heather O’Neill and Scott Deacle explains. Published in Applied Economics, the O’Neill and Deacle paper spends a fair deal of time explaining why the authors chose on-base-plus-slugging percentage as their measure of individual effort. This paper also presents evidence to show that there is a relationship between a player’s contract position and their effort. Players show improved performances in the final year of their contract. Both papers present impressive amount of data. One of the features of sport is that sports performances tend to be public and measurable. The accumulation of evidence makes it is hard to deny that there is some systematic variation of a player’s performance and that this is related to their contract. It is less clear whether this variation is priced into the contract. Or, as Joel Maxcy and others have noted in the literature, maybe the contracts are structured in such a way to deal with such situations. |

Archives

June 2024

About

This website was founded in July 2013. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed