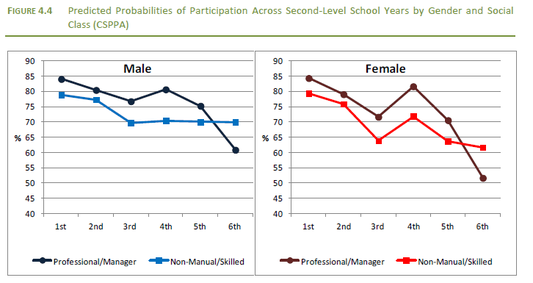

The ESRI report notes that the major participation drop-off points coincide with kids leaving primary school and at the ages of 18 and 21-22, which roughly coincide with leaving second and third-level education, respectively. It is the first drop-off point that I wish to address in this post.

With regard to the fall-off in team sports, one issue that may be a contributory factor is the movement to ‘competitive’ games that often occurs at age groups consistent with leaving primary school. Over the last number of years, the GAA, FAI and IRFU have modified their ‘non-competitive’ games for very young players in order to build up to ‘full’ games over a number of playing seasons. Emphasis, officially, is on enjoyment and skill-accumulation and all players must receive either equal or a minimum, and sometimes a maximum, amount of playing time. Once these sports move to ‘competitive’ level, however, many players that, up to then, were participating regularly, may now find themselves ‘on the bench’or under increasing pressure to perform to a level above their ability. Also, in many towns and villages, once games become full-sided, the local team may be in the position of having too many players for one team but not enough for two teams, or having to amalgamate age groups. When the objective of the club/manager is winning the next game, a number of players can be prevented from continuing to play regularly.

While it is not clear what the IRFU will do to address this problem, the GAA decided a number of years ago to extend its non-competitive ‘Go-Games’ format to matches up to and including under-12 level. Here, all players must play at least half of any game. The rationale was to reduce the drop-off in participation by allowing players more time to develop skills and so be more likely to continue playing when ‘competitive’ matches were introduced. As last year’s u12 cohort was the first that were subject to this new policy, it is much too early to determine the effect of this policy change.

While the GAA’s motive is laudable, it will be interesting to see if the new policy makes a difference. It is to be hoped that the new policy encourages more players to play for longer and improve their skills as a result of this change. On the other hand, while some kids may now continue playing beyond the current ‘drop-off’ point, the effect may be to simply push the problem back by two years. Kids that would previously have stopped playing soon after entering under-12 level may now postpone this decision until they reach under-14 level, as they continue to get playing time for a longer period. If the latter occurs, then the new policy may have a negative impact on ‘better’ players. For players without a major interest in a sport, and who do not engage in as much ‘effort’as other players, there is an incentive to continue playing as they are guaranteed playing time. As a consequence, more ‘advanced’ players may find themselves with less playing time, as a player with less interest in improving their talent must be allowed to

play. In this instance, the new policy may be counter-productive.

While there may be no ideal solution to this problem, it will be interesting to see how the IRFU proceeds.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed