How many economists are there in the world? Or footballers? Or lawyers (some would say too many)? How many “new entrants” are there annually across these professions and make a solid career out of it over time? Of course, there is a greater chance of an individual becoming a lawyer or accountant than a high ranking professional tennis player. World number 531 Marta Kostyuk’s run to the 3rd round at the recent Australian Open generated notoriety for it’s rarity and got me thinking if there is a “regulars only” effect in professional tennis where breakthroughs into the lucrative top 100 are uncommon. Is it more likely that the number 531 ranked player in the women’s game can make the 3rd round of a Grand Slam tournament than it is in the men’s game?

The analysis started with the assertion that in prize money terms about 100 male and 100 female players every 5 years (prime cycle) make a career out professional tennis. Sponsorship or endorsements have not been counted given that good players, who rank consistently highly attract these offers, where as those outside the top 100 do not command a media premium – Anna Kournikova may argue that however.

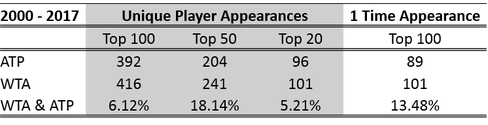

This analysis was conducted from data covering 18 seasons from 2000 - 2017 using year end rankings as per the ATP (male) and WTA (female) rankings. Year end rankings were chosen for consistency purposes.

At a basic level the data demonstrates that it is “easier” for a player to have a chance at launching a successful career in the WTA than in the ATP with 6% more female players making it into the top 100 at some point throughout the 18-year study. Whilst this represents more churn it does tell us that the opportunity to gain entry into a “career” status is greater. This is backed up by c13.5% more WTA players* making the year end top 100 just once than for those in the ATP. WTA players may not have stayed there due to the increase in competitive balance but they enjoyed the tournament privileges and chances to play in the more lucrative tournaments that come with the top 100 ranking.

While the odds for female players are better in terms of opportunity, almost a fifth of all of the players to have made the top 100 in both lists across the last 18 seasons appear once and have little chance of appearing there again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed