In an edited volume on The Economics of Professional Road Cycling, Daam Van Reeth sets out some of the reasons for the successful marriage between cycling and television. Cycling needs broadcast technology in a way that other sports do not. A spectator at the finish line of yesterday's stage would have got to see who won the race and the last few meters of cycling. Without technology they would not have known when the leaders would arrive or what happened during most of the four hours of cycling. Contrast this with a spectator at the FA Cup final the previous day. Such a spectator could have watched Leicester defeat Chelsea without ever accessing technology. They could have taken in the 90+ minutes from the comfort of their seat in Wembley.

The cameras located on the motorcycles amongst the riders and in the helicopters above the riders make the broadcast a promotional tool for regional authorities. Van Reeth explains how the Giro took the lead in the displaying of non-sporting information in 2013. Information about the local landscape, buildings, and food feature regularly. A welcome addition when the action can be limited.

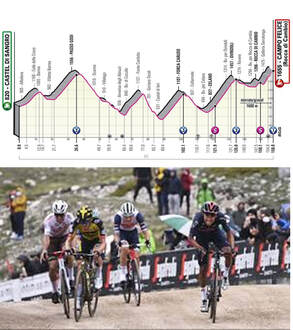

A key feature is that many of the stages in a Grand Tour like the Giro tend to be contested and broadcasted outside prime time for TV. This has its advantages and disadvantages. Broadcasters can view it as an alternative to re-runs of soaps, sitcoms, or crime shows. But it also means that weekday broadcasts attract fewer viewers. Outside the Tour de France, most races struggle to bring in large numbers. This is why the potentially more exciting stages are scheduled for the weekend. The addition of 1.6km of gravel added to the spectacle for the TV audience.

On the sporting side, the main contenders hunted down the breakaway riders on the gravel. The stage winner moved into the overall leader's pink jersey and, at the end of the stage, the top 10 General Classification riders were within one minute of each other. A stage that was well designed and well scheduled for a TV audience.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed