In a recently published book (Money and Football: A Soccernomics Guide) Stefan Szymanski examines, inter alia, the concept of club dominance in European football leagues over the last 50 years. Szymanski reports, using data from 20 European leagues, that an average of only 10 different clubs have won their domestic league titles over this half century, ‘….way below what you would expect to see if there were balance in the league’. The League of Ireland, providing 15 different champions over this period, is identified by Szymanski as one where the number of different winners is considerably above the average. This could be taken to suggest that it is one of the better balanced leagues in Europe.

There are a number of alternative methods available to determine a league’s long-run competitive balance. One such measure is known as the Herfindahl Index of Competitive Balance (HICB). In an extreme hypothetical case where all teams complete the season with the same number of points (i.e., a perfectly balanced league), the HICB value is one. In contrast, the greater the inequity in the distribution of points across teams at the end of the season, the higher above unity is the HICB and the poorer is the league’s competitive balance.

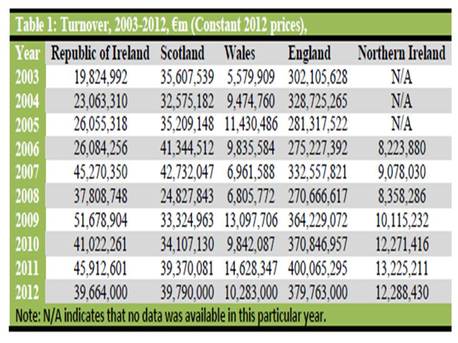

In order to explore the issue of competitive balance for the League of Ireland we use the HICB to compare its degree of balance with a set of neighbouring leagues in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland over 16 recent seasons. The leagues are selected on the basis of arguably possessing comparable playing standards to the League of Ireland.

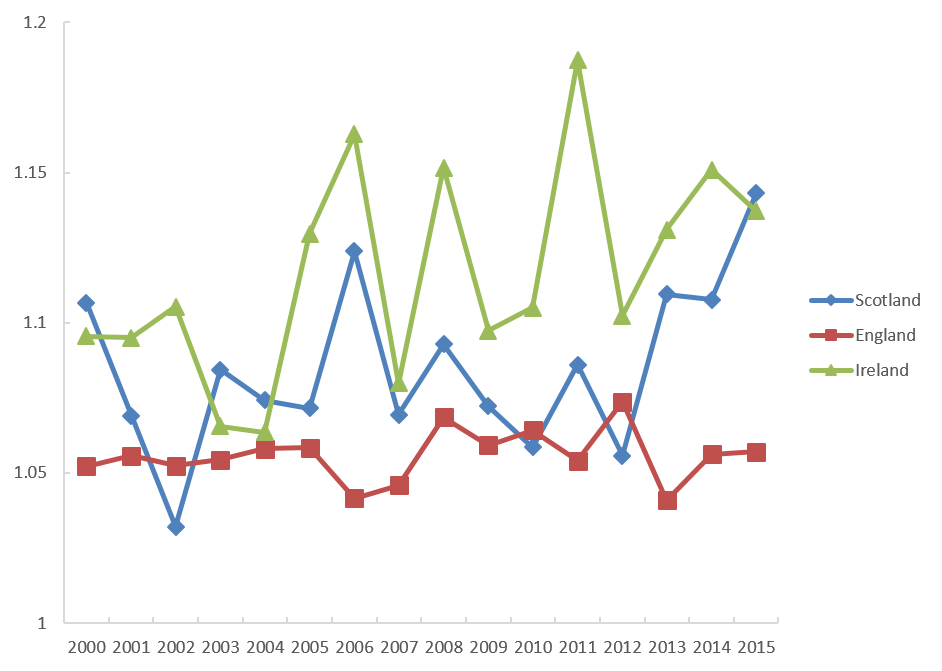

Figure 1 plots the HICB for the League of Ireland Premier Division, the average of tiers three to five in England, and the average of tiers two and three in Scotland. The averages are used here because little material difference in index values is detected across these leagues over the relevant seasons. In contrast to the leagues in England and Scotland, competitive balance is found to be markedly inferior in the League of Ireland. In addition, the league’s index also exhibits a greater degree of volatility over time particularly with respect to its English counterparts.

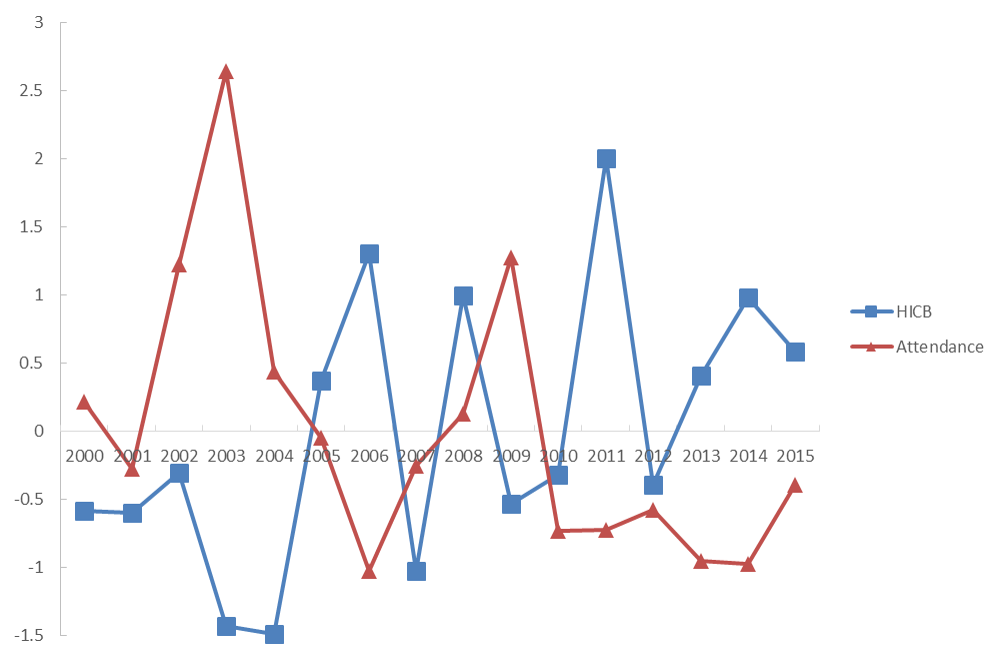

A reason why a league’s long-run competitive balance might actually matter is because of its potential relationship with attendance. A poorly balanced league is likely to prove unattractive to spectators. Figure 3 plots average attendance and the HICB values (both standardized) for the League of Ireland over these 16 seasons in order to discern any informative patterns. The plots reveal an inverse relationship between competitive imbalance and average attendance. The correlation coefficient is computed at –0.60 and is statistically significant at the 5% level using a t-test with 14 degrees of feedom. It should be emphasized that this finding is best interpreted as suggestive since nothing informing the causal relationship between these two variables can be inferred from this statistic. However, competitive imbalance and attendance appear to move inversely in this league.

Farai Jena is a Teaching Fellow in the Department of Economics at the University of Sussex. Her research interests are in the area of applied microeconomics and include the economics of migration, migrant remittance behaviour, and the demand for football.

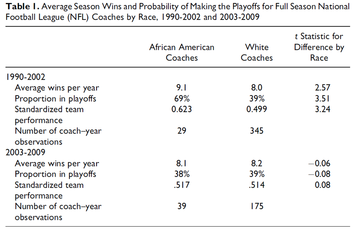

Barry Reilly is Professor of Econometrics in the Department of Economics at the University of Sussex. His research interest include labour economics and the economics of sports. He has published research on developing country labour markets and on racial discrimination in football.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed