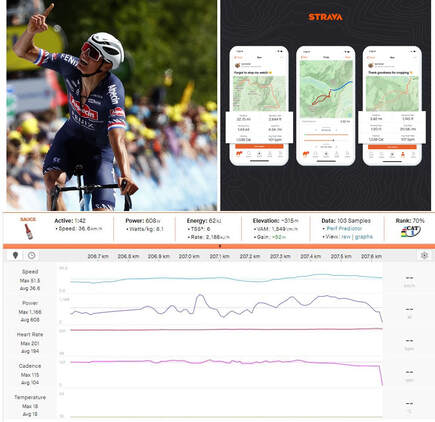

Daron Acemoglu and his co-authors say that the first principle of economics is optimisation. Individual cyclists in La Vuelta are presented with a basic optimisation problem on Stage 10. This stage is an individual time trial. The objective is clear. The cyclist has to cover 31km as quickly as possible. The individual cyclist has to decide how best to use his resources to achieve that aim. He is alone for those 31km. He is the modern Robinson Crusoe. Generations of students were introduced to the principle of optimisation with stories of Robinson Crusoe on a desert island. Crusoe had to allocate his resources in the most efficient manner. He had to optimise.

A crucial extension in the Crusoe story arises when Man Friday arrives on the island. Roughly speaking, Crusoe treats Friday as a slave rather than an autonomous individual (the author, Daniel Defoe, had links to the slave trade). In this scenario, Friday was effectively one of Crusoe’s resources. The “common good” was decided by Crusoe. Alternatively, a kinder interpretation might view them as a team. Cycling teams have their leaders (Crusoes) and “domestics” (Fridays). This is evident in most stages, e.g. in sprint finishes a team's sprinter will have his lead-out man. But it is in the team trial that teamwork is most clearly illustrated. Again, La Vuelta 2022 provides an illustration of team optimisation. Stage 1 was a team time trial. Here the team had to get the majority of its members to cover 23km as quickly as possible. The optimisation problem in the team time trial was one of pure coordination. How best to combine the physical resources of the individual members to achieve an objective?

The variety of optimisation problems in a three-week Grand Tour makes it ideal for illustration purposes. The time trials account for 2 of the 21 stages in La Vuelta 2022. The other 19 stages involve strategic consideration because they introduce competitors. This brings us to the second principle of economics laid down by Acemoglu, Laibson, and List. The second principle is equilibrium and the authors illustrate it by discussing the free rider problem. “Free riding” is the essence of road cycling. For 19 stages of La Vuelta 2022, individual cyclists will seek to “free ride” on the efforts of others. Considerable effort can be saved by drafting behind other riders as they cut through the air. But, if everyone follows this strategy we will effectively get a slow bicycle race. In equilibrium, a less than optimal amount of the public good will be provided. It will look as if there is collusion amongst the peloton for most of the race. This does not happen for a variety of reasons but for the moment let us focus on the way financial incentives are used to encourage competition.

The race organisers provide financial incentives to encourage competition (economists love incentives). The race organisers sprinkle small prizes along the route. The riders who get first to various intermediate points each day are awarded points in various (jersey) classifications and financial rewards. There are also rewards for riders who get away in smaller groups from the main peloton. Changing the payoffs for players is a standard solution to such problems as most first year students will soon discover in their textbooks.

Or consider the incentives offered by race organisers to encourage cyclists to break away from the peloton. What does the logic of collective action say (to borrow Mancur Olson’s book title) will happen? It says that the group size will be small because of the free rider problem. What does the data say? A 2019 Journal of Economic Psychology article examined the issue by examining 783 early/first breakaways from the peloton (see previous post). It found that the optimum size is 10 (with another 190 left in the peloton). Theory and data align.

Optimisation, free-riding, and empiricism. Economics and/or cycling.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed