We will be taking our usual Christmas break and will return on Monday the 11th of January. We would like to wish all of our readers a happy Christmas and prosperus new year.

|

By David Butler

We will be taking our usual Christmas break and will return on Monday the 11th of January. We would like to wish all of our readers a happy Christmas and prosperus new year. The 2nd sportseconomics.org workshop on sport and economics will take place on Friday 22nd of July 2016 at University College Cork.

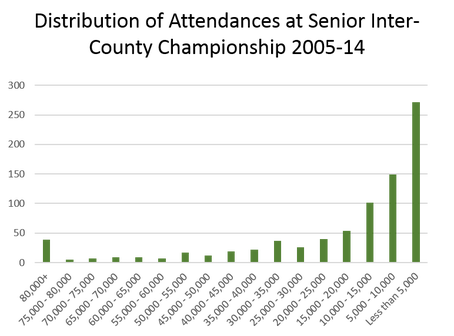

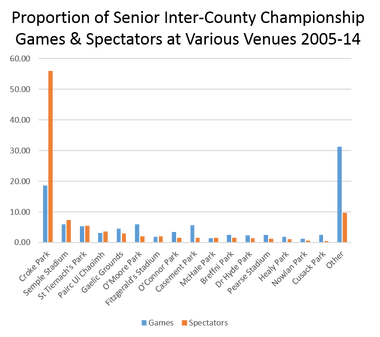

The purpose of the workshop is to discuss and stimulate research ideas from those working in the areas of sports economics, sports management, coaching, public health, and related fields from Ireland and abroad. Further details on the keynote and call for papers will be issued in the New Year. The Organising Committee: David Butler, Robbie Butler, John Eakins By John Considine This week Jose Mourinho complained that his work was sabotaged by players that no longer seemed to listen to him. Within days he lost his job. Only days earlier, a colleague emailed me wondering if anyone was listening to us or reading the blog given what has been previously posted about GAA stadia (here). That post got to the heart of the matter. The GAA builds stadia because it does not pay the players. Much of the revenue generated by the GAA finds its way into the development of stadia. The GAA approach to stadia got plenty of coverage in the Irish Examiner this week. Paul Rouse started the ball rolling (his recent book on Sport & Ireland is reviewed elsewhere on this blog). Rouse raised many questions about the proposed new "M50" stadia and the GAA's stadia policy in general (here). The following day, in the same newspaper, Brendan O'Brien returned to the issue (here). O'Brien noted how other stories, again in the Irish Examiner, pointed to the competing financial demands on county boards. One of these demands is the cost of preparing teams. At the top of the page where O'Brien's article appeared there was story explaining how Tipperary spent over €1m preparing their inter-county teams in 2015. Under Paul Rouse's piece the previous day, Jackie Cahill documented how Wexford spent over €800k preparing their teams. Earlier this month the Irish Examiner documented that the expenses in Limerick were also over €1m (here). Remember the €1m per year, per county, figure is for teams composed of players that are not paid for playing. It is questionable whether or not the GAA could afford to go professional. However, there is more money being generated by the inter-county game than is being spent on expenses. Therefore, extra revenue tends to find its way into facilities (playing facilities and stadia capacity) in a similar way to the way that increases in Premier League TV broadcasting money tend to find its way into players (transfers and wages). When it comes to GAA stadia, the key feature tends to be capacity. One is unlikely to find a dining venue or a shop selling county merchandise. These activities tend to be left to the street traders. Over a decade ago, Seamus Coffey and myself documented the demand for larger GAA stadia capacity (here). In the intervening period, this work has been regularly updated but the broad picture remains the same. There is a need for some larger stadia to accommodate All-Ireland and Provincial finals. But, the majority of games involve less than 20,000 spectators. This is illustrated in the figure below that presents 10 years of events (i.e. there could be more than one game played). Less than 50 events attracted 80,000+ over the ten years whereas there were over 250 games with 5,000 or fewer. Another feature of the data is that the Dublin footballers are a key driver of the larger attendances. In recent years, Dublin footballer have only played in Croke Park. Add to this, the fact that the latter stages of the All-Ireland series take place in Croke Park and it is easy to understand why that venue dominants the GAA landscape. Croke Park dominates the men's senior championships in terms of the games it holds but particularly in terms of the numbers that pass through the turnstiles. This is illustrated in the picture below where it is difficult to see some of the bars for many of the stadia because of Croke Park's dominance. The difficulties involved in having a more "rational" distribution of stadia are many. Paul Rouse and Brendan O'Brien drew attention to the range of vested interests. Another difficult is tradition (Rouse also refers to this aspect). Wearing my economist hat, I might suggest that one 55,000 seat stadium in the largest urban centre in Munster (Cork) should hold all Munster championship games. However, wearing my former player hat, I would not swap playing in Thurles, against Tipperary in a Munster final, for anything. I know footballers who feel the same about Killarney and Kerry. And, what about Limerick? Should the GAA divert the smaller games to Limerick in the same way Munster rugby diverts smaller games to Cork? (I'm ignoring that fact that I'll be accused of a Cork bias.)

Then there are commercial difficulties. Take corporate boxes for example. At present, the GAA sells corporate box and premium level seating in Croke Park. These patrons are promised a certain number and type of games. There are only so many All-Ireland finals, semi-finals, and quarter-finals to go around. It would be doubtful if corporate boxes or premium level seating outside of Croke Park could provide a financial windfall. Brendan O'Brien drew attention to the quality of the press box facilities in Portlaoise. It is over 12 years since Seamus Coffey and myself addressed the issue in our working paper. Our paper addressed issues raised in the GAA's Strategic Review. We proposed the (re)development of one major stadium in Connaght, Leinster, Munster, and Ulster. We were less convinced by the proposal to develop two new medium capacity stadia outside of Dublin. However, there may well be a case for one quality stadium on the "outskirts" of Dublin. The outskirts might stretch as far as Portlaoise, Newbridge, or Navan. Or it could be as close as the M50. The key is that it should be part of a wider investment strategy. But it is difficult to get away from the fact that, because of its financial model, the GAA is always likely to have too many larger stadia. by Declan Jordan  The Economic and Social Review (Ireland's leading journal for economics and applied social science) publishes two sports economics articles in its latest issue. One of the articles is written by colleagues in UCC and this blog (the Butler Brothers). The other is an article by Barry Reilly of the University of Sussex on the demand for League of Ireland football, specifically Premier Division football. This paper is particularly timely given current debates within the league and the Irish football community generally on the contents of the Conroy Report on the sustainability of the league. The paper is a very welcome contribution to the Irish sports economics literature. This is the first paper of which I am aware that conducts such a robust analysis of the determinants of demand for the league. This might primarily due to data limitations, with attendance figures for the league only recently being available more generally and being somewhat reliable. It is notable that the attendance data (sourced from extratime.ie) are, for some clubs, estimates from journalists and others in attendance rather than official club or league records. The paper structures the determinants of demand around three groups of variables, expected match quality, outcome uncertainty and opportunity costs for supporters. The findings are consistent with studies for lower leagues in England and in general are unsurprising. The evidence though shatters some dearly held myths about League of Ireland attendances. For example, there is a perception that club supporters would tire of games involving the same Dublin teams too frequently in a season, but the paper finds that derbies (in Ireland these are almost completely between Dublin clubs) are strongly positive effects. Also, live TV broadcast of the game (or another game at the same time) has no significant effect on attendance and the weather seems to be irrelevant (either we League of Ireland fans are a hardy bunch or the switch to “summer soccer” has removed the weather as an important effect). The key findings are that fixture quality, uncertainty of outcome (a better chance of a home win), geographical distance between the teams, recent team performance and seasonal competitive balance have positive effects on match attendance. The paper is comprehensive and should be used to inform decisions on restructuring and reform of the league. The author suggests that there is little evidence from his analysis that an increase in league size in justified and it is hard to disagree – since such a move would necessarily reduce the number of matches that had an important outcome at stake. The striking finding for me from the paper is the importance of outcome uncertainty – where “the perceived certainty of a match outcome adversely affects attendance for matches where the ex ante home win probability is 0.25 or less” (page 504), and particularly that a fifth of matches fall into this category. This is strong evidence against an increase in the size of the Premier Division. The author however goes on to recommend a “sizeable reduction” in the size of the Premier Division – and I think the case is less convincing here. The author doesn’t indicate what a sizeable reduction would be. Currently the Premier Division has 12 teams and the Conroy Report has recommended a reduction to 10 from the 2017 season. Is there a point after which the size of the Premier Division works against it being a credible competition? Greater match quality is assumed to accrue from a greater concentration of playing talent in fewer clubs and that these clubs would then be of closer quality. This may very well be the case but the semi-professional (or for some clubs amateur) status may work against clubs attracting talent, particularly for provincial clubs. A good player may be indifferent to playing with one of the many Premier Division Dublin or nearby clubs but it is more difficult for provincial clubs to attract the better players from Dublin. In his most recent book, using a different measure, Stefan Szymanski noted that the League of Ireland was the most competitive European league, so this would seem to suggest the status quo is working in terms of competitive balance. The Conroy Report refers (and the paper also makes passing reference) to having more games where something is at stake. This is not necessarily increased with fewer clubs (although more balanced clubs would likely mean greater uncertainty of outcome for individual games). The Conroy Report suggests having a break in the season where the division splits in two. In a previous post I suggested an MLS-style conference system with play-offs, which would keep clubs interested longer in the season. Finally, although it is beyond the scope of Barry Reilly’s paper, the question needs to be asked about what the League of Ireland is for. If it is to generate greater interest (measured for example by attendances) then why not exclude clubs that have shown over many years that they cannot generate large crowds. Perhaps this occurs anyway with the loss of clubs like Monaghan United, Sporting Fingal and Dublin City – it is hardly likely that a club like UCD could be run on a commercial basis. However, if the league is intended to provide an outlet at senior level for as many Irish football supporters then a more regional structure is required and would need to be supported. It is relevant to note that only today the Irish Times reports that soccer is the most popular sport in Ireland – though this is hardly visible in attendances at League of Ireland grounds. It is these questions that need to be answered before the league is reformed once again. The history of League of Ireland reform suggests that tinkering with league size or structure will fail to address medium to long-term sustainability without a fundamental soul-searching about the league among those who run it and care about it. Barry Reilly’s paper is a critical element in the discussions on what changes are needed, as (finally) we can point to evidence on which to base decisions. By David Butler

Over the years sport has acted as a useful domain to study decision making under risk and uncertainty. This is because incentives are at work in semi-structured environments where participants mostly have had the chance to learn. A curious and quite old finding, where people make such ‘real-life’ probability estimations, comes from studying the behaviour of gamblers at race tracks. The End-of-Day effect involves choosing bets that have a lower probability of occurring but higher payoffs, in the later stages of a round of gambling, and is one of many cognitive biases psychologists and behavioural economists have discovered. The problem at hand is intuitively quite simple. Imagine you are at a racetrack where eight races are going to post throughout the day. You have a fixed budget of a €10 bet per race. Let’s assume that you are not having any luck; you are backing favourites and none of them have won! By the time the last race goes to post you are €70 out of pocket after seven previous failed bets. Given that you only have €10 euros left, what do you choose to place your final bet on? Do you a) bet on a horse that is clearly odds on favourite at 1/7, as you have been doing all day, or do you b) shift your preference to an outsider horse who has a chance but is priced at 7/1? If you stick with the 1/7 favourite and are successful (which is most likely to happen) you will leave the racecourse with €14.28 (a lot less than the €80 you arrived with). If you switch to the 7/1 long-shot however there’s an outside chance you will leave with your original budget of €80. Of course, as it’s a long-shot it’s more likely you’ll leave the race track penniless! The most famous study on this idea was conducted in the middle of the 20th century when William McGlothin (1956) collected data on 9,605 horse-races, primarily from California tracks from 1947-1953. He was interested in the stability of risk taking behaviour over a series of events, in particular the constancy of subjective probability and subjective utility of those who place bets over the course of a day. On-course betting allowed the preferences of gamblers to be measured that were of equal expectations but different probabilities of success. McGlothin (1956, 615) concluded that “the group behaved in a manner such as to increase the variability of their assets as a series of risk-taking events preceded”. In the last race risky decision making increased as bettors shifted towards horses that held longer odds. Further evidence of the end-of-day effect in the race course is provided by Muktar Ali (1977) who analysed 20,247 horse races over a five year period. Again, horses with a high objective probability of winning were seen to be understated and horses with a lower objective probability of winning were overstated. This relationship was shown to be robust across different race tracks and alternative race conditions, supporting the original McGlothin (1956) study. Why is this interesting to economists? The answers is because such behaviour is inconsistent with the predictions of subjective expected utility theory - a central theory in the discipline. This theory suggests that when offered a risky gamble we make a rational choice by weighing up probabilities and likely consequences, consistently choosing the best outcome. In the thought experiment given above, you should treat the races independently. On average punters wouldn’t back a 7/1 shot over a 1/7 shot in the first race, so why would more people do so in the last? The problem is because it is psychologically challenging for any race-goers to treat their wealth level and races independently; logically one should not seek out a long-shot in the final race but rather incur a small gain of €4.28 (but retain a net loss) and treat the first race of the next meeting you attend as your next bet. While the End-of-Day effect is outside of the predictions of the traditional utility theory in economics, it can be accommodated by Prospect Theory. Perhaps we shift toward more risky bets as the day goes on because we form reference points in regards to profit making? The reference profit is commonly zero. If gamblers are incurring high loses by the last race of the day they would prefer to substitute away from gambling on favourites, towards horses that have a lower likelihood of winning, in an effort to return to this reference point of zero. My advice would be to keep the End-of-Day effect in mind the next time you head to the race track, casino or even when you see your bookmakers offer a boosted price for long-shots in later races. By that last race of the day you’ll probably see punters who just don’t care about their final €10 and irrationally take a big punt that could, but probably won't, come off! . By David Butler I gave a short lecture to senior cycle secondary school students (high school) on the Economics of Sport yesterday. The talk focussed on prize money distributions across sports. The event took place in University College Cork and my slides from the talk can be viewed below. By Robbie Butler

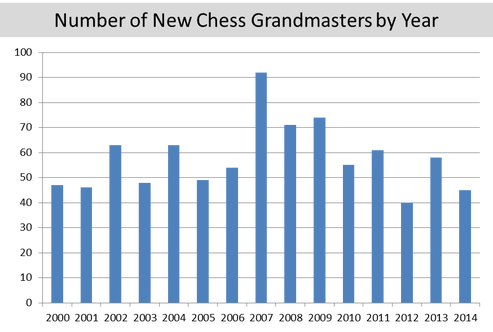

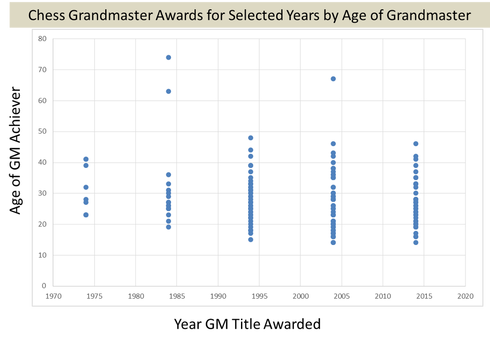

The Ryder Cup was in the news today, despite the fact we are not in a Ryder Cup year, when it was announced that the Marco Simone Golf and Country Club (not to be confused with the former AC Milan striker), on the outskirts of Rome would become the first Italian golf course to host the event. Italy will become only the third mainland European country to host the biennial event, after beating off competition from Austria, Germany and Spain. The economic forecasts have already begun, and the value of the event to the local and national economy. To be fair to the event, which is the biggest in golf, it does not possess some of the cost associated with the ‘biggest’ events in other sports. For a start it’s just three days long. While investment in some sport infrastructure is required, most of this is temporary, and can be dismantled afterwards. Just one venue is also required. It’s likely the majority of spectators will be from outside of Italy, as was the case in Celtic Manor in 2010 and Gleneagles in 2014. It’s estimated that the value of the event to Wales in 2010 was around £80 million pounds with less than 30% of spectators from the host country. Scotland claims to have had a similar positive experience. An impact study by Sheffield Hallam University's Sport Industry Research Centre (SIRC) suggested that the 2014 event was worth in excess of £100 million to the Scottish economy. I’m sure Rome and Italy will hope for an even better result. By John Considine A couple of months ago the Financial Times did a special report on the state of chess (here). The front page headline referred to the growth of chess. A story, inside the FT supplement, claimed that chess attracts seven times more regular players than golf worldwide. Elsewhere, Adam Thomson makes the point that getting to professional level is easier nowadays. He may have a point but looking at the number of new Grandmasters, one might wonder if the sport has moved past its peak at the upper levels. The years between 2007 and 2009 saw the largest numbers being awarded the title. If we take a slightly longer view it is possible to see the growth of Grandmaster numbers towards the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. The picture below shows the awards of Grandmaster title in 1974, 1984, 1994, 2004 and 2014. It also shows the age (defined as the gap between the person's birth year and the year of the award) of the person achieving the title of Grandmaster. It seems to confirm the FT view that technology has facilitated younger achievement in chess. The outliers in 1984 are Stojan Puc and Eero Book. The outlier in 2004 is Yuri Shabanhov. A full list of those who achieved the title of Grandmaster is available here.

By David Butler

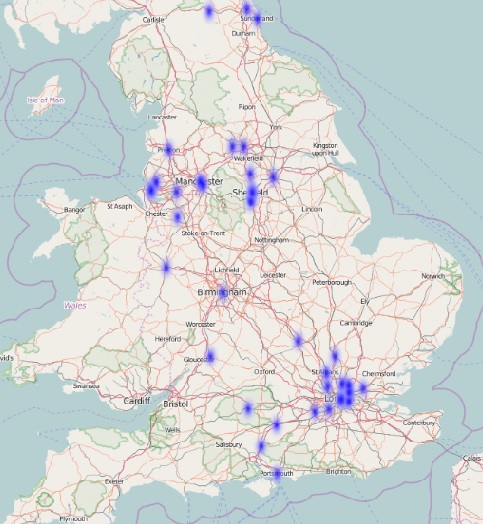

According to my count, 57 footballers currently registered as Irish are contracted to English Premier League clubs. 27 are senior players while the remaining 30 are part of reserve squads, development squads or academies. Some are on loan. The first map below shows the birthplace of these Irish footballers. Birthplace could be considered a proximate measure for where players learned the game and trained from a young age. 21 were born in Dublin, 23 were born in the U.K. and the remaining 13 were born in other cities and towns outside of Dublin but in the Republic. One noticeable trend is the absence of any current Premier League players born in the West region of Ireland. The West region of Ireland consists of counties Galway (city), Mayo and Roscommon (NUTS Level III). Damien Delaney makes sure that the South West region of Cork and Kerry have a presence, albeit minimal. The second map shows the birthplace of the current England squad and recent call-ups. There was 40 English players in the list (Raheem Sterling was removed as he was born in Kingston, Jamaica). Clusters are visible in the urban areas of London, Liverpool and Manchester. Daniel Sturridge is the only player to put Birmingham on the map. By Robbie Butler

A number of months ago I examined Premier League broadcasting rights and the costs that consumers face when watching live football. For those unfamiliar with the piece, I questioned whether consumers were better off following an agreement between the Premier League and European Commission a decade ago to end Sky Sports’ monopoly coverage of all live English Premier League matches. The Guardian recently reported on a related issue of broadcaster Virgin Media querying the current Premier League broadcasting rights deal with UK media regulator Ofcom. Virgin Media are unhappy with the current allocation of rights, where the Premier League sells six broadcasting packages to the highest bidder. They believe the Premier League are limiting supply, and therefore, creating an artificially high price for consumers. Virgin Media want to make all 380 Premier League games available live on television, and have lobbied for a removal of the traditional 3pm blackout in England, wanting the US-style “regional blackouts”. This would mean that fans based in North London for example, would not be able to watch Arsenal or Tottenham live on TV but could watch Manchester United or Liverpool. Virgin Media’s stance is interesting but I wonder will it solve the problem for customers? As mentioned previously, UK customers now pay more in total, and on average, to watch all live games available each season, despite the fact that Sky Sports’ monopoly ended in 2007. Setanta, ESPN, and most recently BT Sport have done little to push prices down for the consumer. Why has competition not worked? The problem lies in the fact that broadcasters compete to buy each of the six broadcast packages but do not compete on the broadcasting rights of individual matches, once they secure the rights. Imagine if both Sky Sports and BT Sport were broadcasting the same live matches. Customers could choose to purchase the rights from the company that was the cheapest, provided the best analysis, overall value, offered best punditry etc. Selling the rights off in tranches of six does little for the consumers. Smaller monopolies are emerging. The current scenario is very much in the interests of the sellers. How much would a TV company pay for a broadcast package if it were not an exclusive right to screen those games? A fraction of what they are now paying. There are a plethora of unintended consequences that could emerge if Virign Media's proposals are adopted. Lower league clubs should continue to fight to retain the 3pm blackout and need only look at attendances in the the League of Ireland since the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards to see the damaging impact televised football can have. Daire Whelan's Who Stole Our Game plots the remarkable decline in attendance at domestic Irish football matches following the arrival of live broadcasts. The Irish 'blackout' was overcome by technology. Technology is again threatening to end the blackout in England. Smaller clubs beware. |

Archives

March 2024

About

This website was founded in July 2013. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed