|

Yesterday's Irish Examiner has some interesting numbers in an excellent piece by Jackie Cahill on an "official" suggestion by Kildare that sponsorship revenues be shared (here). This suggestion follows one by Dermot Earley reported six weeks ago in the same newspaper (here). A previous post on this blog drew attention to the differences in support for various counties presented in Michael Moynihan's GAAconomics (here).

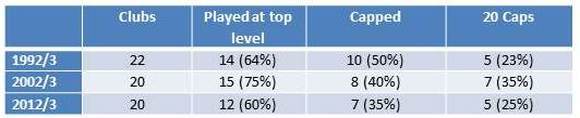

by Declan Jordan  There is a cliche in football that successful players don't make good managers. It is now almost generally accepted that great players don't become great managers - and the rise of Jose Mourinho, Andres Villas Boas and David Moyes along with the long standing success of Arsene Wenger and Alex Ferguson as managers without any or modest playing credentials are often used as evidence. In the recent coverage of the appointment of Roy Keane as assistant manager to Martin O'Neill for Ireland there has been a lot of reference to Keane's abilities as a footballer and as a manager. Probably the greatest footballer we have ever produced has not had a stellar managerial career to date (though not as terrible as Alex Ferguson might want us to believe). The stereotype of course is that great players are frustrated in management by players who are unable to do the things they could do as players. Also, the argument is made that great players are less interested in the mundane detail of football management. There is also a sense that there is an increase in the prevalence of managers who have never played at the high level at which they manage. There may be an element of bias in this as more recent cases such as Villas-Boas and Mourinho are held out as a new type of manager. I've looked at the managers of Premier League clubs at 10 year intervals over the 21 seasons since it began. These are the managers that were in place at the end of the 1992/3, 2002/3 and 2012/3 seasons. The table below shows the number of clubs in the Premier League in each of these seasons. The other columns show the number of clubs whose manager played at least 50 games in any top football division, the number of clubs whose managers earned at least one international cap and at least 20 international caps. The table shows that there has been a decline (in the last 10 years) in the number of Premier League managers who had played at a high level, measured by appearances in a top flight of football or by playing for their country. Interestingly there are quite a few managers each season who played at a high level but were never capped such as Alex Ferguson, Sam Allardyce, Steve Bruce, David Webb, Paolo di Canio and Howard Kendall.

This would seem to suggest that there is a tendency to see more managers without high-level playing experience. However, it's noticeable that that number of managers with 20 or more caps is relatively stable suggesting that where there are managers that have played at a high level the survivors are the ones that have achieved quite a lot as a player. By John Considine The December 2013 issue of the Journal of Sports Economics has a paper examining the difference in salaries for players depending on whether they are predominantly right-footed, left-footed, or able to play equally well with both feet. The paper is likely to spark many talking points. In this post I will present some of the results from the paper. Next week I will examine some of the debate that the paper might stimulate.  The authors of the paper are Alex Bryson, Bernd Frick and Rob Simmons. Bryson, Frick and Simmons conduct their statistical analysis using two sets of data. One data set is a cross section of European footballers. The other data set is a number of years of data from the German league. The authors present plenty of statistical evidence that two-footedness earns players a premium. There are various estimates of the premium but the authors go with 18.6% in their summary. They also evidence of a premium for left-footedness – although the size of this premium varies with the way they perform their statistical analysis. They find the size of the left-footedness premium is greater with the European data set. Their explanation relates to scarcity. They argue that there are a greater proportion of left-footed players in Germany and, therefore, there is less of a premium. Bryson, Frick and Simmons also find that the premium for players depends on the position they play. Forwards have the largest premium, followed by midfielders, with defenders having the lowest premium. One of the benefits of this type of research is that it provides statistical support (or not) for the beliefs of sports people. Most of the above findings are not likely to be controversial. This does not make them any less valuable. However, when statistical evidence supports what most people believe then it tends not to spark much debate. Therefore, it is worth looking at one part of the results that might spark a little controversy. It relates to the premium for being an international soccer player. As a base for comparison the authors use Spanish players who are not internationals. This is their base category. All categories of international players are compared with this group. The authors find that there is a premium for an international player compared to these domestic Spanish players. If we consider these premiums as a measure of ability then what internationals should get the higher premiums? Considering the distribution of FIFA World Cups and UEFA European championships over the last 15 years then internationals from France, Italy, and Spain might be expected to command larger premiums. The results show that the largest premium goes to England internationals (157%). German internationals receive a premium of 114% while French and Italian internationals receive premiums of around 60%. South American internationals receive a premium of less than 50%. Are these “international” results measures of ability or are they picking up something else? It is difficult to say. They seem a little strange given the performance of the respective international sides. By David Butler

Match fixing in football was headline news again this morning as six people were reportedly arrested by officers from the National Crime Agency in the U.K for their involvement in match-fixing in English football. This got me thinking about the incentives match fixers face. Economists have investigated criminal behaviour before, with the most well-known model of crime and punishment being Gary Becker's rational choice approach. Put simply, Becker viewed economic agents as purely rational from start to finish and that engaging in criminal activity was a question of the costs and benefits an individual faces. In the Sky Sports report on the same matter, it is reported that the Daily Telegraph secretly taped a match-fixer and recorded him speaking of the high costs of match fixing in the U.K, when he suggested that “In England the cost is very high... usually for the players it is £70,000.” By Becker’s logic one would assume that top tier games around Europe are not subject to match fixing as the costs to compensate (already highly paid players) would need to be excessive to convince them to stake their reputation. As the benefits of a fixed match in the betting market can be the same regardless of who is playing ( i.e. a 2/1 Arsenal win pay-offs the same as a 2/1 Northampton win), match fixers have a far greater incentive to target lower tier fixtures where costs are lower as compensation for the players would not have to be as great. Also these games would not have the eyes of the world watching. The only greater cost is that a ‘big bet’ on an obscure match is more likely to set off alarm bells for the bookies. To a degree the markets offered by the bookmakers can encourage match fixing, so supply may induce demand – below is a picture of amateur matches in Ireland on this Sunday that Paddy Power is betting on. If match fixing is going to happen given the costs and benefits faced by both parties involved its more likely than not going to happen in matches similar to below. Here is a thought-provoking story, on how Cobb County spends its tax dollars, on the Democracy in America blog (here).

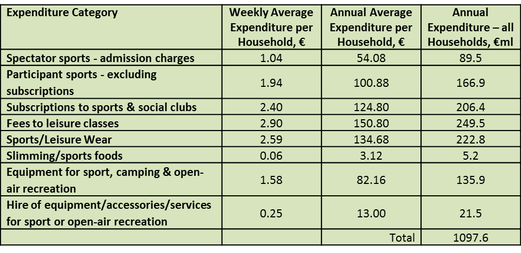

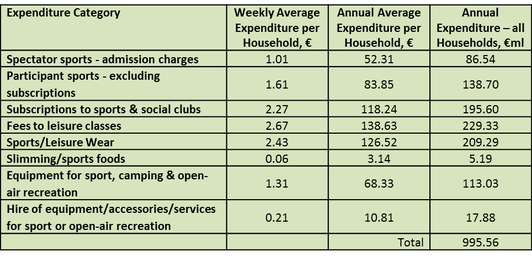

By John Eakins In 2010 Indecon published a report which looked at the contribution that sport makes to the Irish economy. One aspect of their report is the estimate of €1,885.6 million that they placed on the amount of money that Irish households spent on sport and sport-related goods and services in 2008. This was equivalent to 2% of the overall value of consumer spending in the economy at the time. In this blog I will provide an updated estimate of the economic value of sports related purchases using a similar methodology.  Indecon used the Household Budget Survey (HBS) as the basis of their figures and that will be my start point too. The HBS provides information on the average weekly amount spent by Irish households on a large variety of commodities. Isolating the sports related categories and simply aggregating across all households will therefore provide an approximation for the total annual spend. To aggregate I use data from the recent Census (2011) which gives a figure for the number of private households in the state equal to 1,654,208. Eight categories of sports relating spending were analysed and the calculations displayed in table 1 below. All values were taken from the 2009/10 HBS except for the ‘Sports/Leisure Wear’ value. This value had to be projected forward from the 2004/05 HBS as no distinct corresponding category existed in the 2009/10 survey. To find this value it was assumed that the share of ‘Sports/Leisure Wear’ spending in total clothing and footwear in 2004/05 remained the same in 2009/10. As can be seen from the table €1097.6 million is estimated to have been spent by Irish households on the eight sports related categories in 2009/10. This corresponds to 1.33% of personal consumption in those years (taking an average of personal consumption in 2009 and 2010) and 0.69% of GDP in those years (again taking an average of GDP in 2009 and 2010). It is possible to project forward to get a value for say 2012 but this requires making certain simplifying assumptions. In particular one can use the change in the consumer price index for each of the categories above to estimate weekly average expenditure per household in 2012. Thus we are assuming a price change only and quantity purchased has remained the same (which is debatable for many of the goods above although any changes in quantities purchased between 2009 and 2012 should not be too significant). Table 2 displays these calculations. So in 2012 €995.56 is estimated to have been spent by Irish households on the eight sports related categories which

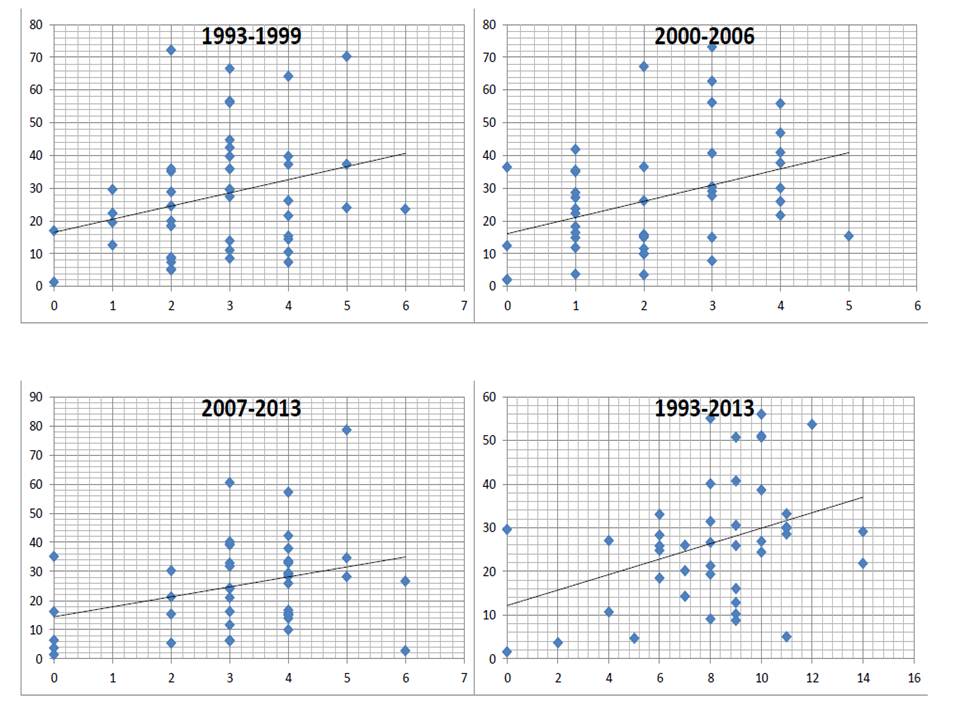

corresponds to 1.20% of personal consumption and 0.61% of GDP in that year. This represents a fall on the 2009/10 figures although in our calculations the primary reason for this has been decreases on the prices associated with these goods. The values are also much lower than the €1,885.6 million estimate providing by Indecon. Even the 2009/10 estimate is almost 60% below this figure. One of the reasons for this is that Indecon adopted a much broader definition of sports related purchases and included a proportion of the money that households spent on items such as travel, books & newspapers, TV licence and subscriptions and school & university fees. It is also the case that Indecon produced their estimates at the peak of the economic boom. A proper comparison with the Indecon results would require further research but in ignoring these secondary effects, the estimates from this blog are probably a little on the downside. However, even allowing for these secondary effects, it is clear that the recent recession has had a negative effect on sports purchases and this blog has provided a first attempt at quantifying that effect.  By Robbie Butler In August I blogged on the divergence in prize money between racing in Ireland and Great Britain. Cental to the post was the arrival of national hunt star Sanctuaire to these shores. Sadly, on Sunday of last week, Sanctuaire was involved in schooling fall after racing at Punchestown. The horse suffered a fractured shoulder and leg and had to be put down. Sanctuaire's short stay in Ireland was seen as something of a coup for Irish racing but puts the economic concepts of risk and uncertainty and the role of luck into sharp focus. Frank Knight's famous 1921 publication Risk, Uncertainty and Profit explains the difference between risk and uncertainty, giving rise to the idea of Knightian Uncertainty. Knight says that: "Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated.... The essential fact is that 'risk' means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomena depending on which of the two is really present and operating.... It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or 'risk' proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all." Harold Kirk paid £170,000 on behalf of Willie Mullins and Mrs Susannah Ricci to take Sanctuaire to Ireland. The owners were no doubt aware of the risk of such a heavy investment but could not put a measurable value on the chances of a fatal fall on the Punchestown gallops while school. This is uncertainty. The role of luck, in every sport, is a critical ingredient of success. One can often wonder what might of been had things gone differently (for better or worse) for so many sports stars. Just ask Jonathan Sexton today... by Declan Jordan  In a previous post I looked at the extent to which Premier League clubs have been increasing the rate at which they change managers. This is part of a research project for which I am controlling for the effect of managerial change on league performance. There have been several studies that have looked at the effect of managerial change on performance such as here and here (both by Audas, Dobson and Goddard). The former paper (Audas, Dobson and Goddard, 1997) found poor recent form drives many managerial terminations, while managerial turnover is more rapid in the lower divisions and that managerial change appears to have a harmful effect on team performance (measured by match results) immediately following a managerial termination. The latter paper (from 2002) finds that: teams that changed their manager within-season are found to under-perform over the following 3 months. Managerial change also increases the variance of the non-systematic component of performance in the short term. The high incidence of within-season managerial change in English football may be a consequence of team owners gambling that an increased variance may help produce an improvement in performance sufficient to stave off the threat of relegation. Using data from 1993 to 2013 (21 seasons) for all clubs that have appeared in the Premier League at least once, the grpahs below show the relationship between team performance (measured by the club's end of season position - from 1 to 92) and whether there was a managerial change in that season.

The data is broken into 3 equal periods of seven years. This means along the horizontal axis the number of seasons in the relevant period that a club changed manager (at least once). The vertical axis is the average league position for the number of seasons in the relevant period. The graphs show a negative relationship between average league position and rate of managerial change over prolonged periods of time. The data is collected as a control while testing other determinants of league performance. It is not possible here to address causation. Do poor-performing clubs change managers a lot or do clubs that change managers a lot under perform? There is little comfort here though for team owners gambling that an increased churn in manager provides sustainable improvement in performance.  By Sean Ó Conaill UEFA as an organisation finds itself in a somewhat curious legal jurisdictional minefield. Although UEFA is based in Switzerland which is outside the European Union the majority of UEFA members are now from states which are members of the European Union (30 out of 54 members). Some of these UEFA member associations who are based in EU member states also happen to be the powerhouses of European football on the international scene and in particular in the club game. In order to achieve a uniformity of rules across all UEFA members associations the rules laid down by UEFA must comply with EU Law. The most famous instance of this is the renowned Bosman Ruling. The Bosman Ruling recognised that those working in football were workers and were entitled to leave clubs at the end of their contract period without the clubs being entitled to compensation just like any other worker. Over the years that followed UEFA and FIFA worked closely with the EU to ensure that the relevant rules governing employment and licensing requirements are not in conflict with EU Law although there are still some exceptions granted to football as an industry (including for example the restrictions placed upon the free movement of players under 23). Although the Bosman Ruling was a victory for player power and the free movement of workers, it inevitably lead to a huge increase in player wages and, along with other factors, a massive increase in the spending by football clubs across Europe. Inevitably this led to an increase in the number of football clubs encountering serious financial difficulties as they gambled on success in order to qualify for lucrative European competitions. UEFA, in response, put in place a number of initiatives in an effort to regulate football, initially from a financial point of view but gradually expanding to encompass all areas of regulation of the game to ensure best practice. One of the areas highlighted for regulation was the area of coach education. As Paul O Sullivan points out herethere are different levels of coaching badges available to coaches across Europe. In order to coach at the highest levels however the UEFA club licensing rules state that coaches must have a UEFA ‘A’ badge. In the case of top tiers of senior football, including European competitions a UEFA ‘Pro’license is required by the regulations. In Ireland for example, clubs wishing to play in the League of Ireland must be coached by a manager who has the UEFA‘Pro’ license and all other coaches involved must possess at least a UEFA ‘A’license. While it is laudable that UEFA have set down minimum standards and there is no doubting the correlation between a greater number of qualified coaches and success at senior international level, a number a legal issues arise. Given that football coaches are entitled to the same rights as any other worker within the EU they have the right not to have unfair and anti-competitive barriers to employment placed before them. Consumers of these services, namely the football clubs who are seeking to employ these coaches, also have rights to access a fair and competitive market. If a market is too tightly regulated access to the market itself will be restricted resulting in increased prices for consumers due to the lack of competition. In addition to the costs issue highlighted by Paul O’Sullivan, which in of itself could be claimed to be an unfair barrier in certain circumstances, the issue of access to the training courses themselves is problematic. In order for prospective coaches to access the UEFA ‘Pro’license course they must have successfully obtained all other training badges. Furthermore, in order to be admitted onto the UEFA ‘Pro’ license course, each candidate must be involved in coaching with a professional football club or a group of elite players. Entry into the course is limited due to the intensive nature, with preference being given to those who are in imminent need a license for the forthcoming season and there are no guarantees that a training course will run each year. In Ireland for example, the course tends to run every second year and takes two years to complete.  The Competition Authority in Ireland has highlighted concerns in recent times of a similar nature in relation to the training and qualification requirements for professions such as Barristers, Solicitors, Architects and Accountants as being overly restrictive and serving as an unfair barrier of access to the labour market. This season alone in the League of Ireland both Cork City FC and Bohemians appointed caretaker managers to the positions of head coach after parting ways with their previous managers during the course of the season. Neither of the respective caretaker managers was in possession of a UEFA ‘Pro’ license. UEFA regulations stated that they could only continue in their position as caretakers for 60 days without the required UEFA ‘Pro’license. Both caretaker managers were precluded from continuing in their roles after that period (despite their extensive experience within the game), and given the restrictive and seasonal nature of the UEFA ‘Pro’ training course, there was no route open to the caretaker manager to attempt to enrol in a course during the season. As a result the clubs in question were forced to appoint a UEFA ‘Pro’ qualified coach from the extremely confined pool of qualified coaches in order to see out the season and comply with the UEFA regulations. It is not argued that the requirement to have a UEFA‘Pro’ License is in of itself an unfair barrier of access to employment. UEFA as the regulatory body is just as entitled to insist on proper qualifications in relation to coaches as the Law Society of Ireland is in relation to Solicitors. The limited access to the training courses; the relatively high cost of the training course; the strict requirements of the UEFA Club Licensing system and the limited pool of already qualified candidates however all serve to create a closed system which could be seen as a natural monopoly and an unfair barrier to employment and competition. Sean Ó Conaill lectures Law and Irish at University College Cork. He is former secretary of Cork City Football Club. |

Archives

March 2024

About

This website was founded in July 2013. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed