Horse racing fans in this part of the world will be well aware that the 2023/24 National Hunt season ends this weekend in Great Britain and the following weekend in Ireland. Willie Mullins is set to become the first Irish trainer in 50 years to become a Champion British Trainer at the weekend. It is a remarkable feat for somebody based in Ireland that largely ignores national hunt racing in the UK outside of the top races.

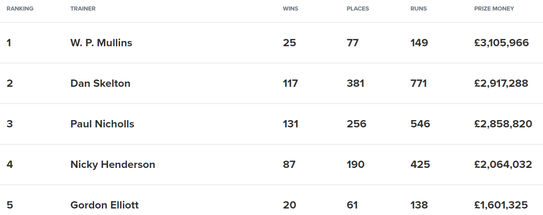

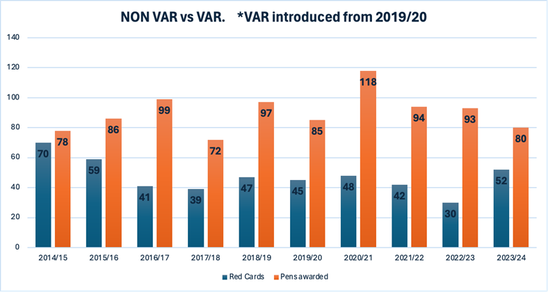

The reason this is possible is because the Champion Trainer titles (in both Ireland and Great Britain) are based on accumlated prizemoney. The current GB standing are presented below.

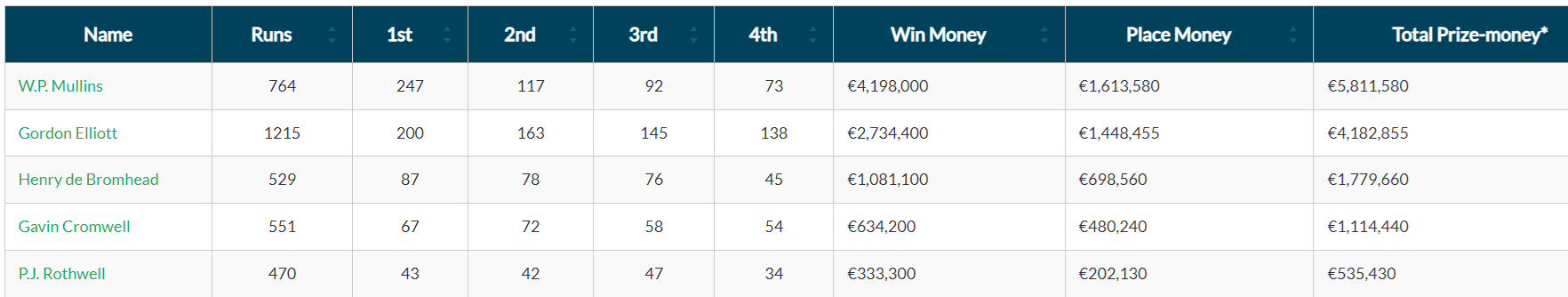

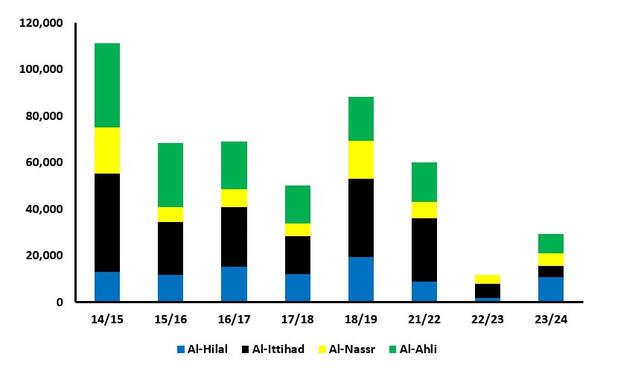

The same metric is used in Ireland. The current standings are below. Again Mullins leads the way.

Competition design matters. Differences can really effect outcomes. Even in the same sport.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed