We hope all our readers have a very enjoyable summer and enjoy the 2020 UEFA European Championship.

|

As is customary at this time of year, we will take our summer break and return on Friday 30th of July 2021.

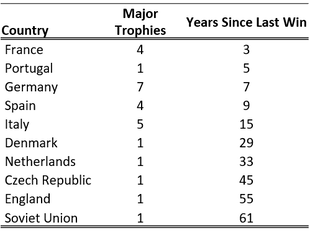

We hope all our readers have a very enjoyable summer and enjoy the 2020 UEFA European Championship. By Robbie Butler With Euro 2020 finally upon us - a year later than expected - I took a look at the betting odds. France our now favourites with many bookmakers (around 9/2), with England (5/1), Belgium (13/2), Spain (15/2), Italy (15/2) and Germany (8/1) making up the top six in the betting. As of June 2021 11 UEFA members have won either the World Cup or European Championship. (For simplicity, I assume West Germany are the same as Germany, Soviet Union are Russia and Czechoslovakia Czech Republic). Only Greece (winners of Euro 2004) are not at Euro 2020. England are the only other winner that stand out, having only won the World Cup. The other nine winners have all won at least one European Championships.  It made me wonder are England actually second favourites? And are Belgium good value at 13/2 having never won a major trophy? The table to the side lists major winners competing at Euro 2020 and the number if years since their last success. Only the Soviet Union (Russia) have waited longer than England. Their 2-1 (AET) win over Yugoslavia at the inaugural European Championships in France in 1960 is now more than sixty years ago. England are now 55 years post Bobby Moore lifting the Jules Remit Trophy at Wembley. While Spain have shown large gaps can be bridged - 44 years separated their European Championship wins in 1964 and 2008 - one would assume a special group of players is needed to get over the mental hurdle of decades of underachievement. I am not so sure the current squad of England players is that group. The next few weeks might prove me wrong. Enjoy the Euros! By Robbie Butler

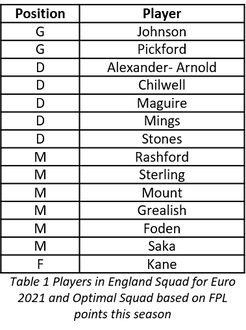

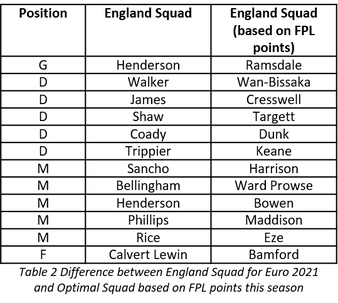

Our 5th sports economics workshop in 2019 was focused on demand issues in sport. It was great to see one of the papers presented at the workshop - considering attendance demand in British horse racing - recently accepted in Applied Economics. The paper abstract reads: "We estimate a model capturing influences on attendance in British horseracing. A fixed effects regression is employed in analysing data containing information on attendances at 23,999 race-days (2001–2018). The patterns of demand are similar to those found for other sports, for example, attendance is higher at weekends and in warmer months and is sensitive to the quality of the racing. Further, attendance falls when races have to compete with some televised sport of national significance. Controlling for a large number of characteristics, the pattern of results on year dummies implies considerable decline in public interest in attending race-days over the period. The pronounced negative trend in attendance suggests a need for modernizing the sport including attention to animal welfare issues, which might partly account for apparently growing public disillusion." The full paper can be found here. By John Considine  Economics is what economists do. That statement is attributed to Jacob Viner. My guess is that Viner never saw a game of hurling but his statement could be amended to describe sporting games. Hurling is what hurlers do. So, what do they do? A good place to start is a paper published last month in the International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport. The data in the paper is from all senior inter-county championship games for the 2018, 2019, and 2020 seasons. The primary purpose of the paper is to distinguish between winning and losing teams in terms of a range of performance indicators. However, it can also be used to give a picture of what constitutes the small-ball & stick game two decades into the 21st century. Hurling, like economics, is ever changing. On average there are 74 shots (or score attempts) per 70+ minutes of a game. Sixty-seven (67) of these shots cross the opponent’s end-line for either a score or a wide (zero points). Then, the game is restarted by a puckout. There is a wealth of analysis on what happens with these restarts. Heat-maps detailing where on the playing area the puckout is directed. Tables showing who wins these puckout and how it differs depending on the distance the ball travels. It is a prime example of how the game has changed. If the data was collected for the late 20th century then the figures in the rows for short puckouts would be close to zero. In those days, "going short" meant dropping the ball 70m away rather than 85m away! The authors note a considerable shift towards shorter puckouts in 2020. The acceleration of the longer-term trend is probably due to the pandemic but no explanation is offered in this paper (maybe a further paper is coming). The pandemic had three important implications. First, it changed the competition structure to reduce the number of games. In 2018 and 2019 a round-robin regional structure determined who progressed to the later All-Ireland stages. In 2020 the regional competitions became single-game knockouts with success in the regional competition determining the stage of entry to All-Ireland competition. Second, the pandemic meant that the games were played in autumn/winter compared to the summer. Third, the pandemic also meant that the games were played without spectators at the venues. My speculation is that the first two might have slightly contributed to longer puckouts but that the absence of crowds contributed to shorter puckouts in a big way. Speculation. There is also tabulated data and graphs detailing how possession is lost or turned over to the opposition (84 turnovers per game). For example, possession is frequently lost in the tackle. It is the third most frequent way possession is lost or turned over. It is a very important part of the game. However, there is not a statistical difference between winners and losers. As Paul O’Brien and his co-authors say, “Tackling is not a significant factor that differentiates winners and losers, despite being portrayed in the media and public discourse as such”. I wonder will we hear and read less of "the team that wins the tackle count wins the game"? It would be interesting to see how the authors would code the "tackle" if they viewed games from the 20th century. My guess that there would be very few modern day tackles where bodily contact dislodges the ball. A current favourite tackling technique is to use the arm, that is not holding the stick, to make contact with an opponent. The further back in time that one goes, one is likely to find that players kept both hands on the stick when attempting to turnover possession. Frequently, it was the stick that made contact with the opponent. This was done with varying degrees of force and legality. Not only could it turnover possession, it discouraged players from trying to retain possession themselves. The ball was transferred as quickly, and as far away, as possible. Different times. The game evolves. What players do defines the game. Hurling is what hurlers do. A good picture of hurling in 2021 is provided by Paul O'Brien and his co-authors. By Stephen Brosnan This week, Gareth Southgate finalised his England squad for the upcoming European championships. There was considerable media coverage surrounding the challenge facing Southgate in trimming the provisional 33-man squad down to the final 26. Much of the discussion centred around the wealth of options England have at right back and whether Liverpool’s Trent Alexander-Arnold would make the final squad. I have previously discussed England squad selection (here) with the results suggesting that much of Southgate’s success has come down to selecting players based on form rather than reputation. This piece explores whether Southgate has again opted for form over reputation in his squad and sets out some potential reasoning for the inclusion of some players at the expense of this season’s ‘in-form’ players. Table 1 shows that 14 out of the 26-man squad (54%) would be selected for the optimal squad based on FPL points. However, three players (Kieran Trippier, Jude Bellingham, Jadon Sancho) ply their trade outside of the Premier League so have not accumulated any FPL points. Excluding these players means that 61% of Southgate’s squad would have been selected for the optimal squad. These figures suggest that Southgate has lived up to his promise to select players based on form rather than reputation.

Table 2 compares players selected for the actual Euro squad with players selected for the optimal squad based on FPL points. Overall, there are twelve differences between the actual squad and optimal squad. However, if we dig a little deeper into the data three key underlying factors emerge for these differences. Firstly, as previously mentioned, there are three selection differences resulting from the inclusion of players playing outside of the Premier League. Secondly, squad rotation amongst Champions League chasing clubs may explain the inclusion of a further four players that did not make the optimal squad. Dean Henderson (started less than half of Manchester United’s games), Kyle Walker (only played back-to-back 90mins once for Manchester City in second half of season), Reece James (13 games didn’t complete 90 mins), Luke Shaw (11 games didn’t complete 90 mins) all made the squad despite not accruing enough FPL points for the optimal squad. Thirdly, the inclusion of Jack Harrison, James Ward Prowse and Jared Bowen in the optimal squad at the expense of Jordan Henderson, Kalvin Phillips and Declan Rice may be explained by the FPL points system. FPL is weighted heavily towards rewarding attacking returns for midfielders thus holding midfielders tend not to perform very well in the game. The one player that may justifiably be feeling disappointment at not even making the provisional 33-man squad is Patrick Bamford (Leeds United). Bamford has outperformed expectations this season with 17 goals and 11 assists in the Premier League, ranking only second to Harry Kane in FPL points. However, he was unable to displace Dominic Calvert-Lewin from Gareth Southgate’s plans despite Calvert-Lewin only ranking fourth amongst internationally active English forwards behind Kane, Bamford and Aston Villa’s Ollie Watkins. By Robbie Butler

One of the quirks of living in Ireland is our fascination with following English football teams. Many people that are ardent football supporters and fanatical fans of English football teams will often refer to a team like Manchester United, Liverpool or Arsenal using words such as "we" "us" and "our". Their identity and relationship with a club from a different country is real and many frequently travel to England to support their team. Often, the same people display no interest in domestic football in Ireland and do not even follow their local team. While I am not guilty of ignoring the domestic game, I do refer to an English team using words such as "we" and "our". Around 1986 I started to follow Liverpool and have continued to do so ever since. The connection I feel is real and is something that I suspect I will have my entire life. And I am not alone. As a child of the 1980s and 1990s most people I knew supported an English team. In the 1980s Liverpool were the most popular choice - for obvious reasons. As the 1990s progressed Manchester United fans started to emerge in greater numbers. Again, like Liverpool of the 1980s, success is probably the driving force behind this but I wonder if there is also an element of path dependence? In 1968 Manchester United won the European Cup. If a 10 year old had started to support the Red Devils in 1968, by the early 1990s they would have been in their mid-30s and possibly have children of their own. Did they "pass" their fandom onto the next generation? I am already guilty of this. Liverpool's success in 2019 and 2020 has made this much easier but I suspect it might have happened anyway. This makes me wonder what jerseys we are likely to see in Ireland in the years ahead? If the 1980s generation were predominantly Liverpool supporters due to the club's success, we could see many more young Liverpool fans during the 2020s. The 2030s would then see the next generation of Manchester United fans. And my observations last week support this somewhat. I was at U6 training last weekend. The jerseys on display included Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea (x2), Manchester City and Inter Milan. The first two are easy to explain. Liverpool and Arsenal were big in the 1980s and remain popular. There was no Manchester United jersey. Maybe a lack of recent success is driving this or the age profile of the current fanbase. Chelsea and Man City are interesting. Growing up I didn't know a single Chelsea supporter and just one Man City fan. I did know fans of Liverpool, Man United, Arsenal, Tottenham and Celtic. I even knew some Newcastle, Blackburn and Norwich City supporters. The clubs that are followed reflect the times were live in. There are now lots of Chelsea and Man City fans in Ireland. Many are younger supporters of the game, particularly in the case of Man City. If path dependence is working here, Ireland might see a second wave of Man City and Chelsea fans sometime in the 2040s and 2050s. This would mean Liverpool in the 20s, United in the 30s, Chelsea in the 40s and City by the 50s. |

Archives

March 2024

About

This website was founded in July 2013. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed