Adam McCarthy is also a UCC graduate from the BComm (International) degree.

In 1956, Simon Rottenberg’s seminal article stated that sport leagues are a business anomaly in that no club can succeed economically if there is a significant gap in quality between teams. Rottenberg hypothesised that sporting talent must be distributed equally among the contestants of a sporting competition to make it attractive for supporters. However, in many professional football leagues, only a few teams are effectively competing for the championship. An extreme example is the German Bundesliga, where Bayern Munich have won ten championships in a row. Nevertheless, the league still had the highest average attendances in European football from 2013-18. Similar observations can be made in other European football leagues.

One explanation for this is that, besides the championship race, there are further sub-competitions in professional European football leagues, such as qualifying for UEFA competitions and avoiding relegation. The theory of Competitive Intensity (CI) takes this into account by looking at “the degree of competition within the league/tournament with regards to its prize structure” (Kringstad and Gerrard, 2004, p.120).

In an effort to quantify CI, the senior author of this article and colleagues introduced and refined an ex-post measurement of seasonal CI, the CI-Index (CII), in a series of studies (Wagner et al., 2020, 2021, 2022). It is derived from the final standings of each season and weighted by a matchday ratio representing the matchday on which each sub-competition was decided. The weight is intuitive and the model can portray individual contributions of each sub-competition to CI. It is flexible and can compare different league structures but does not consider league evolution.

The CII model allows us to break down and analyse sub-competition contributions to CI. Our analysis of the Bundesliga shows, for the seasons from 1998/99 to 2021/22, the championship race generates, by far, the lowest values. The sub-competitions closer to the middle of the table, such as direct and indirect qualification for the Europa League, show the highest values.

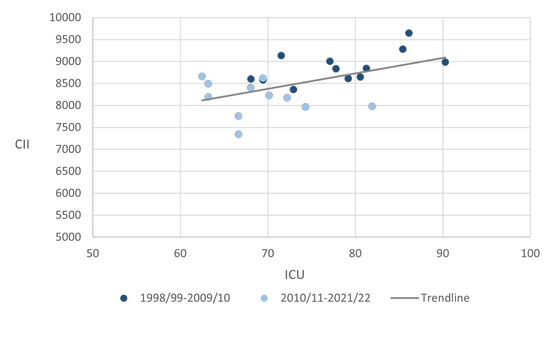

Another model to measure CI was proposed by Scelles et al. (2011). It is called intra-championship competitive intensity (ICCI) and consists of 2 parameters, intra-championship uncertainty (ICU) and intra-championship fluctuations (ICF). They are not combined to form a single measure, but are used separately. In an effort to get a more comprehensive picture of CI in the German Bundesliga, we correlated CII and ICU for the time between 1998/99 and 2021/22 (figure below).

As can be seen in the figure above, CII and ICU have a mildly positive correlation for the German Bundesliga in this period. Both measures have declined recently, which is to a considerable extent attributable to Bayern Munich’s domination in the championship race. Yet, the illustration also shows that the competition should be far from boring because both measures observe a considerable degree of competitiveness when all sub-competitions are taken into account.

Of course, further research is necessary to solidify the findings described here and to further refine CI analyses. Nonetheless, it is obvious that CI measures are useful when comparing leagues and drawing conclusions on how to foster competitiveness and demand from a regulatory and business standpoint.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed