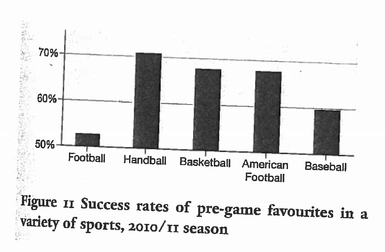

They summarise their conclusions by stating that, almost half the time, the team that is not as well prepared – or has worse players, a raft of injuries, or is just not as good – ends up winning. I find that hard to accept and do not think it is supported by their own data. This data, for obvious reasons, is not presented in full but is summarised in charts.

Now if they had said that any given game was decided on a 50/50 basis, I could accept that. So, if one team was vastly superior in skill, then the other team would need an outrageous amount of luck to beat them. This is consistent with the sort of results achieved in Spain by Barcelona and also with the major upsets quoted by the authors. However, that is not how they phrase their conclusions.

In any event, the reasons why even strong favourites will not always win are not just down to chance. In football especially, the underdog has the possibility of playing for a draw as goals are such a rare event. This is in contrast to sports where territorial dominance almost inevitably leads to victory (rugby and hurling are clear examples). Apart from playing for a draw, a so called upset can be down to many factors other than chance.

The underdogs may have a better tactical plan. I am fairly sure Barcelona were strong favourites to beat Inter a few years ago but the defensive strategy of Inter won out. Mental attitude may also play a part with favourites being over confident and so not preparing as well as they should. All in all, I do not accept that the poorer team ends up winning almost half the time. This is not consistent with the data presented and the finding needs to be more nuanced.

(Bill Keating worked as a statistician with the Central Statistics Office.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed