Another journalist from The Guardian, David Conn, has written on this subject before. In his book Richer Than God he weaves together the many strands that go to make up the private and public funding of football. Conn explain how the professional clubs suck in greater and great amounts of revenue while the facilities for local football are starved of cash. Read his chapter on 'The Beautiful Game' for a grim account of the reality. Elsewhere in the book Conn talks about how the public funding of the game has changed. His explains how public funding has been rechannelled to special projects for which local authorities bid. Ironically, it was Manchester's success in winning the Commonwealth Games that allowed them to build a stadium that was then handed over to Manchester City. Private interests benefiting from special projects made possible from public funding.

In his recent piece Owen Gibson talks about football paying the price for delivering the promises of increased participation attached to the 2012 London Olympics. That London 2012 failed to inspire a generation seems to be accepted. Gibson himself wrote about it last December (here). However, this was predictable. In late 2011, Lord Moynihan, the chairman of the British Olympic Association, forecast that London 2012 would not increase participation because politicians failed to provide funding and a lack of links between schools, local sports clubs and volunteers (here).

Again, it is worth reading the account provided by David Conn in his book. Conn talks about the lack of facilities at local level and contrasts this with what was spent on London 2012. A Football Foundation commissioned survey estimated it would cost £2bn (later revised to £7bn) to bring the facilities up to a decent standard. Conn also documents how prior to bidding for the Olympics, Tony Blair's strategy unit produced a document called 'Game Plan'. Conn quotes a sentence from the review of the evidence and the conclusion reached in the document: "It would seem that hosting events is not an effective, value for money method of achieving a sustained increase in mass participation". Yet, money that could have been spent to upgrade facilities was spent on the Olympics. So, why should football (or any other sport) carry the can for over optimistic political promises and political failure to deliver the relevant resources?

Only last week Moody's brought us another reminder of the lure of bidding for international sporting events for questionable return (here). Moody's estimate that the benefits to the Brazilian economy, from the FIFA World Cup, will be relatively small and temporary. They also highlight the downside risks. The demonstrations that surrounded last year's Confederations Cup in Brazil suggest that not all of the citizens agree with this type of public expenditure.

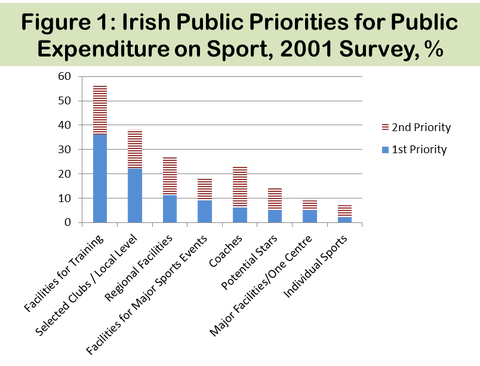

So what priorities have the public when it comes to public expenditure on sport? Maybe they should be asked. Thirteen years ago the Irish government commissioned a survey of public opinion on the issue. Around that time the government was considering building a national stadium as a centre-piece of a sports campus in Abbotstown. The government broadcast the results of one survey question. That question asked if the public was in favour of the government plans for the stadium. It was a Yes/No type of question. Around 70% of the respondents were in favour of the stadium. However, when the public was given a choice of how to allocate the funding the results were different. One part of the survey asked the respondents to list their 1st and 2nd preferences for funding. The results are presented in Figure 1 below. 'Facilities for Major Sports Events' and 'Major Facilities in One Centre' did not seem to be high on the Irish public list of priorities for the allocation of public funds.

For a variety of reasons the stadium at Abbotstown was never built. Instead, Lansdowne Road was renovated. In the years that followed, the government provided large amounts of funding for facilities at local level. While the geographical allocation of some of the funds might display a political bias, there is little doubt that many of the facilities around the country improved. The Irish policymakers deserve credit for shelving plans for a third major stadium in Dublin (regardless of the exact reasons for the decision). They also deserve credit for increasing the funding for other facilities. It is only fair that if we blame them for the rain then we give them credit for the sunshine.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed