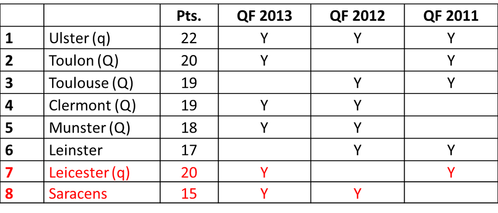

The table below outlines the current position of teams prior to this weekend’s fixtures (Q denotes qualified as group winner, q denotes qualified but final pool position not known, those in red are currently best pool runners up):

In a previous post, I discussed how the competition has come to be dominated by Irish and French teams in recent years and that the circumstances that have led to this may have been at the root of the decision of English clubs not to participate in, at least, next season’s Heineken Cup. Looking at the table above, it is noticeable that the top six teams are either Irish or French, with two English teams currently in the best runner-up positions.

The table also shows whether each club has qualified for the quarter finals in the previous three seasons (Y denotes qualification). The first thing that stands out is that all eight clubs have reached the quarter final stage in at least two of the last three seasons (info on previous seasons available here). Though Ulster is the only team to have qualified in all three seasons, others may have done so had the pool-stage draw been kinder. For instance, in 2010-2011 and 2012-2013, Leinster and Clermont were in the same pool with one knocking the other out. In 2011-2012, Leicester was in the ‘group of death’ with Clermont and Ulster.

There are several reasons as to why this outcome has prevailed. Irish clubs benefit disproportionately from the Heineken Cup, allowing them to, up to now, keep their best players on centrally-allocated contracts at relatively high salaries. As well as this, given the relative weakness of Connacht, the other three provinces are almost assured of automatic entry to the competition, which the clubs see as their main priority. This allows them, often under IRFU instruction, to rest players for Rabo 12 games so they are in peak condition for Heineken Cup and international games. In contrast, English clubs, whose main priority is likely their own Premiership, do not have this luxury, as only the top six Premiership clubs can qualify for the Heineken Cup by right.

On the other hand, French clubs, who also place much emphasis on their own Top 14 title, are subject to a much looser salary cap (€10m v €5m (approx.) for English clubs) allowing them to invest in greater quality and quantities of players, particularly from the Southern Hemisphere. It is believed that the three French clubs in the table above, as well as Johnny Sexton’s Racing Metro, are the only ones to have reached the salary cap.

Given recent trends, and with the struggles of Welsh and Scottish clubs and no English participation in the near future, there is a fear that competitive balance in the Heineken Cup will be reduced and that this will impact match attendance and TV viewership, with possible knock-on effects for the value of TV rights and sponsorship. On the other hand, many

rugby fans may accept reduced competitive balance in return for better quality matches, as may be the case with football’s Premier League.

Should recent trends be reversed and, if so, how could this be achieved? A change in tournament structure, qualification procedures and revenue allocation has been mooted to placate the English teams. Another possibility, though it does not seem to have been explicitly mentioned, may be the introduction of a salary cap for pan-European competitions, different to those applied to national competitions. This may reduce the ability of French, and possibly Irish, teams to field star-studded teams in European competition, or at least it will reduce their average quality, though they would still be free to do so in the Top 14 and Rabo 12. No doubt this would be strongly resisted by the affected clubs.

In recent weeks, the IRB has got involved in the matter to overcome the current impasse. In particular, it has supported the Wales Rugby Union in its conflict with the Welsh regions who wish to participate in an Anglo-Welsh competition against the wishes of its union.

While the current disputes seem set to continue for the foreseeable future, roll on the weekend!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed