However, there have been question marks about Nigerian players' true ages for many years now. Indeed there are strong suspicions that African football,and to a lesser extent other regions, have flouted the age rules for many years. In the 2013 tournament, 3 players from each of Morocco, Congo, and Nigeria were sent home from the U17 World Cup for failing the age test. In 2009 MRI bone scans were introduced to test players were the age they claimed to be.

It may not be surprising that countries would want to use older players, since there is a physical advantage for older players in underage tournaments. Indeed, there is a substantial literature on the 'relative age effect', a topic on which my colleagues on this blog have published research. FIFA rules dictate that a player is eligible for a competition if he or she was born in the designated calendar year, so for the U17 tournament in 2015 players must have been born on or after 1 January 1998 (17 years previously). This means players born earlier in the year (in January for example) can have up to 12 months age advantage (and associated physical advantage) - details on player eligibility is available on page 20 here. There is now substantial evidence that football squads are over-represented by players born in the early months of a calendar year relative to the general population.

What might be expected is that countries who are looking to enter players who are older than they actually are is that they would state an age earlier in the calendar year. For example, in this article it is reported that the Syrian squad for the U19 World Cup in 2012 included six players born January 1, 1993 and that the entire team had January birth dates. That approach seems to be a little bit obvious of course, so perhaps it would be better not to draw attention to your squad by spreading the month of birth out.

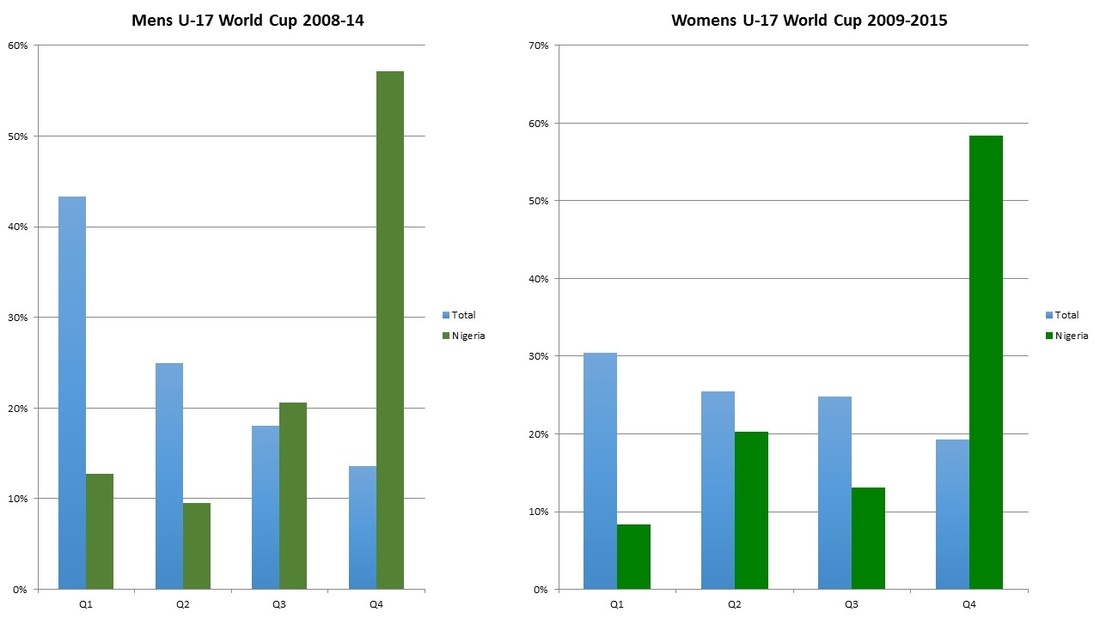

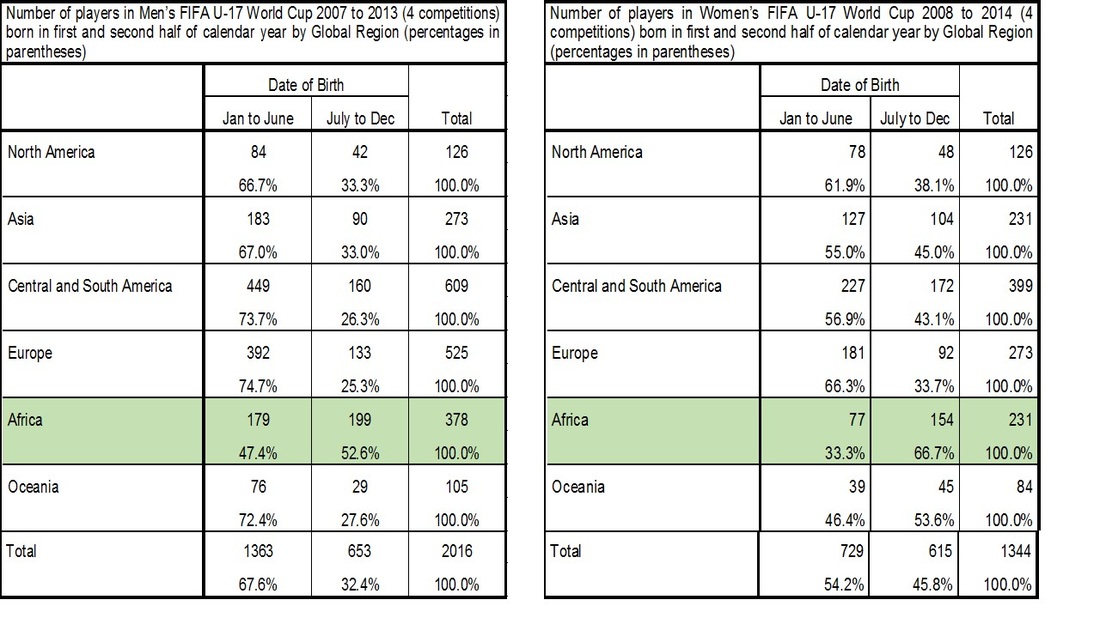

The graphs below show the profile of month of birth (by quarter) for four editions of Men's and Women's U-17 World Cup Finals from 2007 to 2014. There are 24 countries in the Men's World Cup and 16 in the Women's. It is noticeable that the age dispersion is greater for women, more players are born in the later quarters of the year (the difference is statistically significant). The graphs show quite a remarkable difference between the dispersion for Nigerian squads and other squads (excluding Nigeria). Nigeria appeared in all of the four Women's Finals and three of the four Men's Finals. The graphs show that Nigeria had a statistically different month of birth distribution than the average of the other countries.

It is difficult to know the reasons for Africa's exceptional result. If age fraud is a substantial problem there then perhaps the ages being registered are designed to deflect attention by having much less January birthdates. It may be that the birthdate registered is less important where it is different than an actual birthdate. In the absence of age fraud, perhaps there is less physical difference between African athletes of less than a year's age difference, or perhaps African football has avoided the traps of other countries that tend to select more older players and thereby lose younger players to the game. These latter explanations though would likely result in a flat distribution (similar to the dispersion of months of birth in the general population) rather than having such a large proportion in the second half and final quarter of the calendar year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed